I sometimes think that we are entering another golden age of dictionaries and encyclopedias. I don’t just mean Wikipedia which has been written about elsewhere and perhaps trumps everything. I have in mind journals like Annual Reviews, book series like the Oxford Handbooks, or even curated online sources like the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. I find myself again and again drawn to these sources to find out what is going on in various areas of my own field and other fields and I continually recommend them to students of all ages.

In this post, I thought I would poke around these sources and their history. My questions are: how do different fields summarize what they know and how and when did these ways of summarizing emerge. My knowledge of the actual history is a bit spotty, so I’ll mainly try to provide a little data and search for some patterns.

Before diving in, here a few takeaways:

Literature reviews as standard elements of academic papers seem to have emerged relatively recently, but they have taken off since then.

The journal Annual Reviews was founded back in the 1930s mostly for the natural sciences, but it has found new markets in recent years.

Handbooks also have a longer history, but have similarly seen a boom in this millennium.

Online resources like Wikipedia seem to have significant advantages in decentralizing and continually updating the process of knowledge accumulation relative to traditional books and journals, but their academic equivalents seem to be slower in gaining a foothold perhaps because they do not assign credit very well.

Note: My focus here is on summarizing the academic frontier of knowledge. For that reason, I mainly ignored encyclopedias and textbooks, which tend to be aimed at the non-expert or student.

Literature reviews

The standard way of summarizing knowledge in academia is a literature review section of a journal article (or book or dissertation). They have become so ubiquitous and tedious that many recommend that they be omitted altogether. Who wants to read one more canned summary of the literature?

Yet, the twofold purpose they serve (or served) is clear. First, so much has been written on any given subject that many readers require a brief guide to what we know. (And the author’s review of the literature provides a quick test of whether they know what is going on - are they missing or misinterpreting important works?) Second, the literature review helps to situate the present research by identifying the gap in the literature that is being filled.

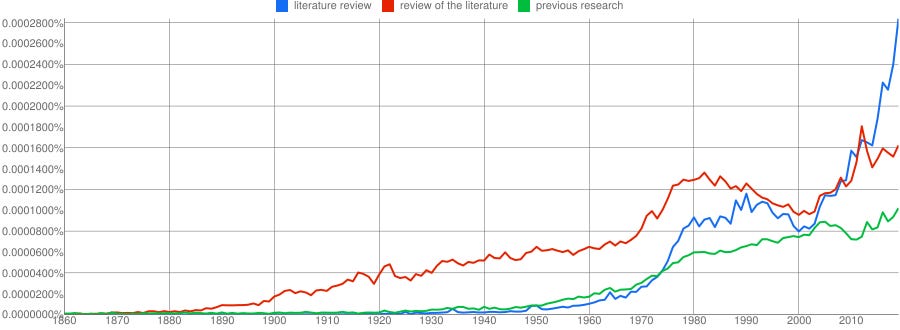

Figure 1 shows trends for the phrases “literature review”, “review of the literature”, and “previous research” from the Google ngrams database. The idea (or at least the terminology) seems to emerge with modern disciplinarity and has taken off in recent years, though much of this is presumably due to the expansion of research in general.

Figure 1: Google n-gram of the terms “literature review”, “review of the literature”, and “previous research”

Because the ngrams are based on books, I tried this exercise with the same search terms on the flagship journals in economics (AER), political science (APSR), and sociology (ASR). The results, see Figure 2, were broadly similar with very few hits in the 1940s and 1950s, an increase in the 1960s and 1970s, and a plateau by the 1990s (the recent spike in the AER might be artefactual - I think JSTOR may have started including proceedings here as well).

Figure 2: Mentions of “literature review”, “review of the literature”, and “previous research” in flagship journals.

I can imagine a couple of reasons why distinct literature review sections emerged somewhat late. In the past, the amount of research and the qualities of the researchers meant that such summaries were unnecessary. Everyone who mattered knew what they needed to know. Similarly, the small and closely networked set of researchers meant that framing one’s contribution wasn’t as necessary. But as I recount next, as early as the 1930s, a biochemist could worry that there was already too much to be familiar with.

I’d add that putting together a good literature review used to be much more difficult. An older colleague of mine, Ken Janda, mentioned to me that his first publications were a book entitled “Cumulative Index to the American Political Science Review, 1960-1963” (with updates in 1968 and 1976) and indices to Annual Conference papers. He also wrote a book entitled “Information Retrieval: Applications to Political Science” (1968) devoted to retrieving information from an Abstract of Literature that he helped to develop. Scouring compilations of abstracts seemed to be the state of the art until recently.

Though literature reviews are now ubiquitous, potential breakthroughs are on the horizon. There have been some attempts to produce automated summaries of literatures. The ultimate goal of the company Elicit is to “to automate and scale open-ended reasoning with language models - synthesizing evidence and arguments, designing research plans, and evaluating interventions,” but they have begun by automating the literature review, which scholars can use for free. Meanwhile, Kriev promotes a dynamic knowledge map as a better way to summarize knowledge.

Annual Reviews

Of course, literature review sections of journal articles are not the only way to summarize knowledge. The aforementioned biochemist, J. Murray Luck, created the Annual Review of Biochemistry in 1932. As he put it, “We shall cope with the information explosion, in the long run, only if some scientists are prepared to commit themselves to the job of sifting, reviewing, and synthesizing information; i.e., to handling information with sophistication and meaning, not merely mechanically.” (By ‘mechanically’, I think he is referring to the collections of abstracts, which I mentioned above.) His Annual Review was intended to do just this by producing articles describing the state of the art in various areas of biochemistry on an annual basis.

He similarly founded an umbrella organization to produce these reviews in other fields. Biochemistry was followed by Physiology in 1939 and Microbiology in 1947. Figure 3 shows the subsequent expansion of Annual Reviews to the 51 that are published today (one, Computer Science, was discontinued after only a short run). The current millennium has seen the fastest growth with about 40% of the titles adopted since 2000. This is the current golden age that I hypothesized at the start.

Figure 3: Cumulative Evolution of Annual Reviews

The journal was mostly the domain of the biological sciences early on, though it soon embraced the physical sciences. Table 1 presents the current titles, their dates of adoption, and their classification by Annual Reviews as biological, physical, or social sciences (or some combination).

Table 1: Annual Reviews by Subject Area

An early exception to the focus on biological and physical sciences was Psychology which was added in 1950. It would take until 1972 for another social science, Anthropology, to join the club. My own discipline, political science, started only in 1998. Figure 2 also shows the trends in the social sciences (including a few journals listed in multiple categories). Today there are 11 Annual Reviews focusing on social science.

Notably absent from the list are the humanities which perhaps do not fit well with Annual Reviews’ original scientific orientation.

These journals certainly met a need. The website of Annual Reviews notes that 15 of their publications are ranked #1 in their field by Journal Citation Reports and 35 are ranked in the top 5 in multiple disciplines. The journal impact scores are uniformly high, ranging from 2.4 for Law and Social Science to 30.1 for Astronomy and Astrophysics with a median of 13.

Handbooks

Handbooks may be the traditional way of summarizing a field’s current knowledge. I am not sure if handbook is a term of art, but here I am thinking of a printed volume that collects state-of-the-art findings at the time of publication. The difference from a textbook is that it is aimed at experts and ignores pedagogy (though the line between a handbook and a graduate level text may be fuzzy).

The history of handbooks goes back further according to the ngram below (Figure 4), though the term handbook is more capacious and refers to less academic forms as well. A colleague pointed me to a Handbook of Social Psychology from 1935. My own professional organization published several state of the discipline handbooks in 1975, 1983, 1993, and 2002. The history of these handbooks is an area where I need to probe a bit deeper.

Figure 4: Google ngram for handbook

But back to my main point, we seem to be living in a golden age for handbooks. One of the most prominent examples is the Oxford Handbooks series, launched in 2003 by Oxford University Press. As they put it,

Oxford Handbooks offer authoritative and up-to-date surveys of original research in a particular subject area. Specially commissioned essays from leading figures in the discipline give critical examinations of the progress and direction of debates, as well as a foundation for future research. Oxford Handbooks provide scholars and graduate students with compelling new perspectives upon a wide range of subjects in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

In less than two decades, they have released nearly 1300 volumes containing over 43,000 chapters. They are neither short (they typically run around 800-900 pages) nor cheap (hardcovers go for around $150).

Their subject matter, however, differs from the Annual Review series. As Figure 5 shows, the series is dominated by the social sciences and humanities with very few devoted to the natural sciences (16 are labeled physical science and 9 as neuroscience). The leaders meanwhile are psychology (218), political science (129), religion (121), philosophy (103), and literature (98).

Figure 5: Titles in Oxford Handbooks

These handbooks seem to be quite popular, at least in political science. The decision to publish so many of them so quickly suggests that they are selling well. Among scholars, they don’t have the negative aura of an edited volume and being chosen to edit or contribute feels like a mark of distinction rather than a burden.

Oxford is in fact somewhat late to the game. Both Sage and Routledge/Ashgate have been publishing Handbooks for a bit longer. Given their longer history, it was harder to get a good sense of their titles. Figure 5 shows the classification of titles in Routledge Handbooks Online, totaling about 1800 volumes, some going back to the 1970s. Unlike Oxford, there is a strong representation of engineering.

Figure 6: Titles in Routledge Handbooks Online

My sense is that Oxford managed to beat its competitors in this market by naming higher profile editors who subsequently recruited higher profile contributors. The academic imprimatur of Oxford may have helped as well.

Is there a difference between the Annual Reviews and these Handbooks? Handbooks presumably aspire to a bit more permanence. They are not designed to be updated and only a few (by my count 29 in the Oxford series) have seen second editions. Oxford has recently launched an updating initiative to ensure “continued relevance and accuracy of the material”, but I am skeptical, given the amount of work required and the (lack of) incentives for contributors. Another difference is that the reviews of the literature in handbooks tend to go further back in time. The Annual Reviews are more about capturing the research frontier and describing a new path forward.

A commonality is that both are heavily curated. The editorial boards of the Annual Reviews typically commissions articles, though, as I learned personally, they will consider pitches. Handbooks are run like edited volumes with the editors in charge of choosing contributors. Indeed, neither the Annual Reviews nor Handbooks are peer-reviewed in the traditional double-blind sense. The main form of review is the editors’ choice of appropriate and competent experts, though editors may make suggestions on draft submissions.

Online Summaries

An alternative type of research summary might take advantage of the web’s ability for decentralized aggregation of information and real-time updating. One of the early and successful attempts is the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. founded in 1995. Its aim was to produce a comprehensive set of reviews of topics in philosophy written by experts and vetted by subject editors and an editorial board. The articles are commissioned and reviewed - and so it is not decentralized - but it is continually updated and previous versions are archived. It is thus a dynamic reference work. In 2018 it contained nearly 1600 entries and is widely used within and outside of philosophy.

Given its success (both with readers and in winning grants for funding), I am not quite sure why this model has not penetrated other fields. Perhaps philosophers are unusually devoted to their discipline (or unusually sensitive to charges that they have not produced knowledge). The discipline may also be close-knit enough that it can assign appropriate credit to contributors (and editors), whereas other fields require the imprimatur of a press or journal.

Wikipedia (founded in 2001), of course, is the standard in online knowledge summarization. Its structure allows decentralized submission of information and editing. Though not explicitly intended to summarize academic literature, Mollick refers to it as “the secret heart of academia”:

He notes an experiment where a single quality Wikipedia article on chemistry influenced the content of 250 published academic articles.

One might worry that the decentralized nature of Wikipedia would lead to it being captured by cranks. But as Mollick points out, by not “filter[ing] what users see, each article is exposed to different views” and “rules and norms subtly encourage extremists to leave”:

My impression is that Wikipedia works relatively well for STEM fields where knowledge tends to be objective and there is an established base of confirmed findings. It seems harder to find summaries of research findings on Wikipedia for social sciences or the humanities.

A recent attempt to replicate something like Wikipedia for the social sciences is SKAIpedia, the Social Science Knowledge Accumulation Initiative Encyclopedia, founded in 2020 by Tatyana Deryugina. Its goal is “to build a wiki that will contain concise, comprehensive, and up-to-date reviews of academic literature.” It contains both overview pages and single-paper pages. Recent overviews include “Pigouvian taxation”, “The Motherhood Penalty”, and “Long-term Effects of Natural Disasters”, each of which lists and discusses key works on the subject.

The founders of SKAIpedia argue that Wikipedia falls short as a repository of academic knowledge in a number of ways. In particular, (i) it is not detailed and exhaustive enough, (ii) it contains too much irrelevant information, and (iii) its prohibition of original research makes synthesis or evaluation of research difficult. As a relatively new initiative, the jury is still out on its success, but I for one am hopeful.

Expert Surveys

A final way to summarize knowledge is to consult directly with experts. In a handful of fields, enterprising scholars have periodically surveyed experts to determine the degree of consensus on findings in the field. While consensus does not equal correctness and surveys are limited in the complexity of the issues they can assess, they provide the closest we have to a collective judgment of what is known.

I believe some of the earliest surveys of this type were conducted by economists and they have been repeated several times since then. Their focus is mostly on the degree of consensus on policy questions like trade and budget deficits. I am also aware of one-off surveys to measure academic consensus on findings/approaches in philosophy (and a follow-up) and political science, for example, my own:

There are a handful of more systematic initiatives. The TRIP (Teaching, Research, and International Policy) project has conducted a series of surveys of international relations specialists on current events. IGM periodically asks a panel of high-profile economists their views on issues of the day. Again, I may be missing other expert surveys.

A new initiative, still in the beta stage, proposes systematizing such expert surveys and allowing scholars to commission them. In the words of Apollo Academic Surveys “Apollo’s mission is to aggregate the views of academic experts in all fields, making them freely available to everyone.”

A recent innovation in this approach attempts to create betting markets on important issues as a way of aggregating knowledge. Tetlock’s Good Judgment Project may be the best known example. Most of the work here has focused on predicting events rather than summarizing knowledge, though one could argue that the two have commonalities. For my thoughts on Tetlock and knowledge accumulation, see here:

A Golden Age?

Table 2 compares these forms of summarization on two factors - how they review the quality of the summary and how they update the summary - as well as the fields where they are most commonly used.

Table 2: Comparison of forms of knowledge summary

The standard literature review as an appendage to articles supposedly undergoes rigorous review (though in my experience reviewers focus more on sins of omission than commission) and is continually updated as others write new articles on the topic with more recent literature reviews. As noted, decentralizing literature reviews in this way can be tedious for both authors and readers, which has led them to be deprioritized (and as one critic argues, the peer review of literature reviews tends to be weak). Yet, new proposals for a cumulative literature review or an automated review may yet revive them.

Annual Reviews overcome some of these problems by centralizing and curating the production of research summaries. They inevitably privilege some points of view and updating tends to be sporadic rather than continual. The popularity of these articles testifies to the benefits of this approach, though they are less relevant to the humanities, where findings tend not to accumulate in the same ways.

Handbooks provide a similarly centralized and curated attempt to summarize bodies of knowledge. Compared to Annual Reviews, they are produced on a longer timeline and thus intended to endure a bit longer. For these reasons, they are more attractive to the humanities and less to the natural sciences. In more technical fields, graduate textbooks may provide a substitute for handbooks.

Online publishing allows for a more decentralized and continuously updated summary of research findings. Wikipedia is the epitome of this form, though it tends to avoid the weeds of its subject matter. Some attempts to provide a middle ground between commissioned reviews and this form can be found with the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy or the recently launched SKAIpedia. I am curious if this is the future of knowledge summarization. Finally, expert surveys can help to codify the sense of what a profession knows, though they are limited to relatively simple conclusions.

I may be burying the lede here, but there is good evidence that how we review knowledge matters. In a landmark study, McMahan and McFarland demonstrated how review articles “identify distinct clusters of work and highlight exemplary bridges that integrate the topic as a whole.” At the same time, they destroy citations to the original work (for a counter, see here). They are a form of creative destruction that pushes knowledge forwards, though at the expense of its creators.

The seeming explosion of knowledge summaries raises some interesting questions. Presumably they allow us to build more bridges and help newbies orient themselves more quickly. But this doesn’t jibe well with work showing a slowing pace of scientific progress. Matt Clancy has a new post making this point (though check out this reply from Adam Mastroianni). These trends may be two sides of the same coin. The quantity of research both makes it harder to produce breakthroughs and necessitates more attempts to summarize.