I know the idea of the Slate Pitch, or counterintuitive take, is the object of much parody, but I remain an avid consumer of counterintuitive theories. And I am probably not alone in advising graduate students to lead their papers with puzzles and emphasize how their conclusions challenge our intuitions.

A question that has intrigued me for a long time is what political scientists consider counterintuitive. What sort of substantive or theoretical finding can be considered a challenge to our existing ways of thinking?

I took a stab at this question by looking at self-labelled “counterintuitive findings” and “counterintuitive results” in some of the major PS journals (APSR, AJPS, JOP). I then tried to put the specific findings into a smaller set of categories.

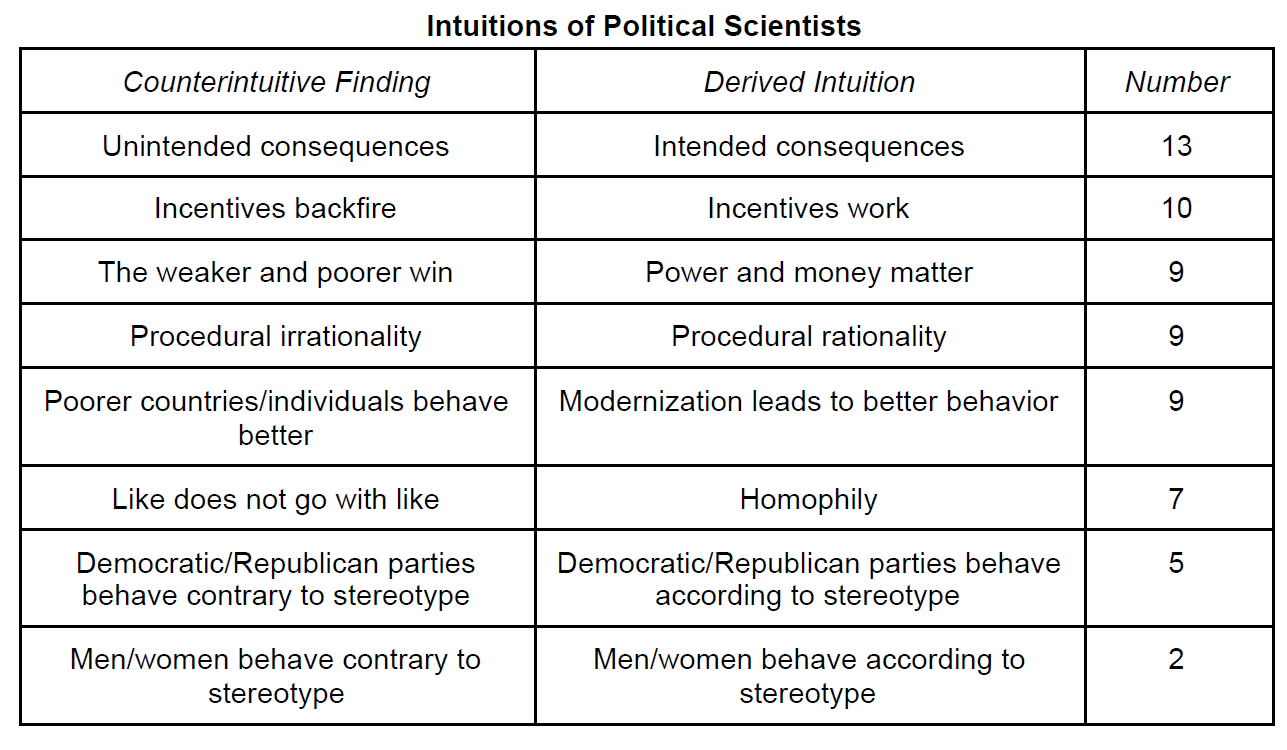

What I came up with is summarized in the table below where I characterize the intuitions which are being overturned. The numbers indicate the number of papers that characterized their counterintuitive findings in this way (altogether I found 71 papers). The most frequent categories refer to cases where the consequences intended by actors did not obtain, where incentives did not have the desired effect, where power and money did not triumph, where actors behaved irrationally, where socioeconomic modernization did not produce better results, and where like did not go with like.

To give a few examples of counterintuitive findings in these categories, consider the following:

Unintended consequences: More unanimous support for war in a country makes war less likely (Schultz 1998)

Incentives fail: Stricter sanctions in trade regimes actually worsen labor practices (Greenhill et al. 2009)

Power and money lose: More spending does not improve a party’s election prospects (Kenny and McBurnett 1994)

Procedural irrationality: More reasoning leads to worse choices (Kuklinski et al. 1991)

Modernization doesn’t help: Poor countries have less political instability (Bienen and van de Walle 1992).

Heterophily: Macro trends do not reflect micro trends (Mondak and Smithey 1997).

Non stereotypical behavior of parties: Republicans increase welfare spending more than Democrats (Browning 1985).

Non stereotypical behavior of men/women: Male politicians experience more conflict between work and personal life than female politicians (Nownes and Freeman 1998).

I’d add that I’m not concerned whether these findings are right or wrong. Only that they are considered counterintuitive and what this tells us about how political scientists think.

If one wanted to characterize the basic intuitions of political scientists (at least as they are expressed indirectly) one gets something very much like Machiavelli and Hobbes (hence the picture above) plus rational choice. Political scientists expect the more powerful actors to win out, They expect outcomes to follow from actors’ preferences. They expect actors to respond to incentives. They expect actors to be procedurally rational and for that rationality to help them better achieve their aims. And they expect socioeconomic factors to have systematic effects on individuals and nations. While these results don’t always pertain - hence the counterintuitive findings - they do provide a baseline from which we derive these deviations. Kuhn would argue that we would abandon these intuitions after we find enough deviations, though I wonder where that would leave us.

I would make a couple of notes about these findings:

First, a caveat. The articles that I studied may not be a cross-section of the profession. Most of them were quantitative pieces and it may be a certain kind of scholar who characterizes their findings as counterintuitive or holds these specific intuitions. I’d be interested in following up on these intuitions with a representative sample, but intuitions are not easy to test.

Second, most scholars follow their identification of a counterintuitive finding with an explanation for why they found it. Often this explanation makes the counterintuitive finding disappear: eg, discovery of an omitted variable, measurement problems, endogeneity, or selection effects. Other times the result leads to new theorizing typically about non-rational or strategic behavior which produces the counterintuitive results.

Finally, the fact that identification of counterintuitive effects leads scholars to more scrutiny of their findings is a good thing. A dash of skepticism always helps. The worry of course is that intuitive findings are not subjected to as much scrutiny. A sort of file drawer effect.

In the end, does it matter what sort of intuitions we have? I would argue that it does. A relatively tight and coherent set of intuitions - arguably what we see here - belies standard portrayals of the profession as divided or balkanized. And the more that scholars are on the same page, the more productive and the less destructive will be debates. Even if these intuitions are not correct, at least political scientists are speaking a common language in describing where they go wrong.

As Kieran Healy writes, “Disciplines fail or break down in the same way that conversations fail or break down: for lack of conversational partners, for lack of interest in a topic, or for chronic lack of agreement on what counts as a useful contribution. While some kinds of failure just lead to embarrassing lulls, the latter sort of failure is potentially destructive of the conversation itself.” A lack of shared intuitions might be this kind of failure.

PS: I’ll soon post the longer paper on which this is based.