Part of political science’s internet lore is a tweet written by Paul Musgrave in the wake of Trump’s election. It no longer exists on Twitter (or X) and is today mainly circulated as a screenshot of a photocopy. It is reproduced below.

The tweet suggests that members of different subfields in political science would respond differently to the threat posed by Trump. Americanists would presumably be least attuned to the threats because of their limited purview, whereas IR scholars or comparativists would be more aware and theorists perhaps most of all.

Many of us have had a good laugh at this tweet. It cleverly gets at some divisions in the profession. But is it true?

We could call the Musgrave hypothesis the idea that the broader the outcomes that one studies, the more that one would be alert to threats from Trump. Theorists would thus be most aware as their subfield covers the history of political thought (should we call it the Levy corollary?). IR would come next given its concern with interstate war. Next would be comparative which studies a broader set of countries, though individual scholars are often limited to one region. Finally, Americanists would be the most limited in their awareness of threats.1

Surprisingly, there is data that we can use to test this idea. In particular, the Bright Line Watch (BLW) set of surveys has been asking political scientists about democracy in America (and elsewhere) for the last eight years. Their sample includes members of all the subfields and so it is possible to determine if there are differences in these assessments across the subfields.

Unfortunately, when I looked at this data, I found limited support for the Musgrave hypothesis. Americanists, comparativists, and IR scholars had relatively similar views on the threat posed by Trump and their assessment of democracy in the US.

The one bit of confirmation I discovered was for the Levy corollary that political theorists had a greater awareness of problems at least in how democracy is functioning. But their fears were not specific to Trump. They extended to democracy under Biden, to democracy in the past, and to democracy in other democratic states. Theorists tended to be more generally skeptical of the functioning of modern democracies relative to empirical political scientists though it was hard to isolate exactly which elements worried them the most. I’ll speculate more on what this means below after presenting the evidence.

The Bright Line Watch

The Bright Line Watch surveys are perfectly designed to test the Musgrave hypothesis. In the wake of Trump’s election, the scholars behind the project - John Carey, Gretchen Helmke, Brendan Nyhan, and Susan Stokes - began fielding surveys of both the public and political scientists in order to “to monitor democratic practices, their resilience, and potential threats.” The “bright lines” of their name comes from their attempt “to identify potential areas of agreement…among experts and the public about the most important democratic principles and whether they have been violated.”

They have since conducted 20 surveys and to my knowledge they are the first to survey all political scientists on matters of substantive concern.2 On average, 709 scholars responded to the survey with an overrepresentation of self-identified Americanists (279) followed by comparativists (187), international relations specialists (135), and political theorists (52) with a smaller number representing other fields or subfields. The numbers are lower for some questions because not all respondents were presented with all options.

Democracy under Trump

How do political science subfields differ in their views of Trump? I will start with the question that is asked most frequently in the Bright Line surveys, a rating of the US political system today where 0 is least democratic and 100 is most democratic. Figure 1 shows the averages for the major subfields over the lifetime of the survey. Political theorists stand out in rating US democracy consistently worse. The other three subfields are grouped relatively closely together, though IR scholars were slightly more positive during Trump’s term and Americanists slightly more negative overall, which is the opposite of our expectations. The gap between the empiricists and theorists is around 10 points on the 100-point scale.

However, this is not specific to Trump. The election of Biden in 2020 led ratings to rise for all the subfields, but with a similar-sized gap.

Democracy in the past

We can probe this even further. Several of the surveys ask respondents to rate the US at previous times in its history. Figure 2 shows these results for one of them. The gap remains with political theorists giving much more negative scores and the other three subfields grouped relatively closely together. The exception is the 19th century where all four subfields were in agreement about the lower level of US democracy.

Democracy elsewhere

We can see a similar pattern in Figure 3 which shows ratings of foreign countries. Political theorists again are something of an outlier, but mainly among the more democratic countries - Canada, Great Britain, Italy, Brazil, Israel, and Mexico (but not India and Poland). They cluster more closely with the other subfields among the less democratic countries.

What is democracy?

Can we isolate where theorists think differently about democracy? The Bright Line Watch also includes a set of questions asking about which of a set of 27 elements are essential to democracy.

Figure 4 shows a comparison of means for the main subfields from the second wave of the survey. Here there is less evidence that theorists or any of the subfields stand out. While there is some variation, nothing really hits one between the eyes.

Disaggregating America’s performance

However, Figure 5 which shows the ratings of America’s performance on these indicators from the second wave returns us to the conclusions from earlier. Theorists are again substantially more critical of US performance on a majority of these criteria, while the other subfields cluster together.

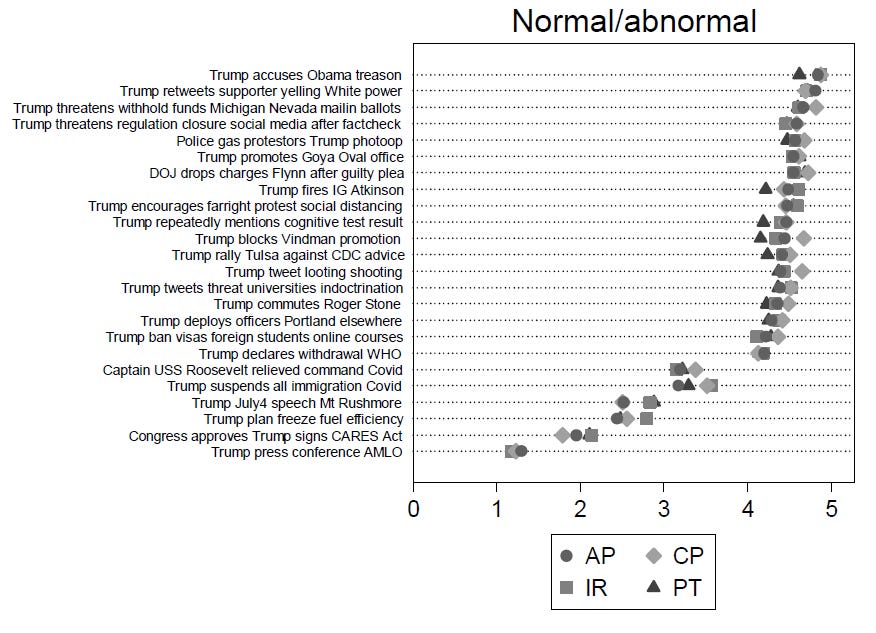

Trump’s weirdness

Figure 6 shows responses to questions about the normality/abnormality of current events from the eleventh wave of the survey towards the end of Trump’s term where 1 means normal and 5 abnormal. One might expect Americanists to see more abnormality given their limited purview, while other subfields might see many of these actions as normal. Here the answers are relatively tightly grouped across subfields and there appear to be fewer consistent differences. If anything, theorists sometimes stand out as seeing events as more normal and comparativists less normal, the opposite of what we might expect.

Conclusions

Contrary to the Musgrave hypothesis, members of the empirical subfields in political science tend to think in similar ways about Trump and democracy in general. As fun as Musgrave’s speculation is, it receives only limited support.

But there is substantial evidence for Levy’s corollary that theorists might see Trump differently and for an even broader hypothesis that theorists have a different way of evaluating democratic performance than empirical political scientists. Theorists differ from other subfields in their much more critical evaluation of US democratic performance and the performance of other democracies across most criteria, but they do not seem to be using a different set of criteria or to view different aspects of US politics as abnormal. One could attribute the differences to either a training or a selection effect.

How should we interpret these results? The fact that the scale for theorists is centered differently from the other subfields may not be important in and of itself. Mostly, the patterns of their responses (over time and across space) correlate with the other subfields. Theorists simply believe that most democracies could be working considerably more democratically than they are.

This more critical view, however, leads to two potential problems. One is that theorists seem to be reading from a different playbook about what democracy is or could be. In their view, democracy can function much better than what we actually see. For such an essential normative standard in the discipline, it is unfortunate that we are using different measuring sticks.

The other problem is that by downgrading most contemporary democracies, theorists leave less space for distinguishing them from non-democracies. Their ratings are not as well-calibrated to the scale used by Bright Line Watch. This potentially allows supporters of non-democracies to claim that they are not uniquely bad; supposed democracies suffer from the same flaws. Apologists for Putin and Xi frequently make such arguments. To be clear, I am by no means grouping theorists together with those apologists; I am just warning of a potential danger. I could imagine theorists responding that we should be more concerned about the real flaws in existing democracies than about charges of hypocrisy.

I would note that in theorists’ skepticism of democracy they are more in line with the views of the public. In a previous post, I showed that political scientists tended to rate US democracy more positively than the public. In this sense, we empiricists may be the ones who are out of touch.

One could potentially put forward the reverse hypothesis. Because Americanists study the US, they may be better attuned to its vulnerabilities and to the challenges that Trump poses.

The TRIP group has surveyed IR scholars and there are some individual surveys of comparativists and political theorists, one of them my own

Good use of the BLW data.

I wonder about the extent to which these subfield differences would be muted if all graduate students were required to take a year’s worth of political theory courses.