Baseball fans are becoming less and less plentiful. I’m part of this trend. I once watched both Yankees and Mets games (on channels 9 and 11), collected baseball cards, and played fantasy (it was rotisserie back then). I barely pay attention anymore and I’d be hard pressed to name a single player for probably half of the teams in the league. I think Bill Simmons has said that it is mainly a local sport now - people follow their hometown team but not the game of the week.

I am, however, fascinated by the history of the league and the role it played in American life. Joe Posnanski’s The Baseball 100 captures exactly what I liked about the sport as he tells stories from the careers of the greatest players. It’s almost like hearing Mel Allen’s voice and the theme to This Week in Baseball again.

Posnanski packs so many good stories into his 800 pages that I felt compelled to write at least some of them down to etch them in my memory. My first thought was to pick one fact about each player, but I decided instead to try to organize my notes into the recurring themes of his book. I think the three main ones are fathers and sons, race, and evaluating greatness. I’ll intersperse those with other interesting tidbits.

A few fun anecdotes as an appetizer

“Tell you what, kid; you get that first pitch close and I’ll call it a strike.” - The umpire to Curt Schilling before his first major league start

“Wind him up in the spring, turn him off in the fall, and in between he hits .340.” - said about Charlie Gehringer, nicknamed the Mechanical Man

The best hitting coaches are bad hitters (Charlie Lau, Walt Hriniak, Charlie Manuel)

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn skipped Hank Aaron’s 715th HR and sent Monte Irvin in his place who was then booed by fans

“How do you expect me to work without my tools?” - Johnny Mize on his array of bats. And my favorite couplet: Your arm is gone, your legs likewise/But not your eyes, Mize, not your eyes.

Dirt disorder: “The farther a person gets from the dirt, the easier the game looks.” - George Brett

“My favorite song? It’s the National Anthem because every time I hear that song, I gonna get two or three hits.” - Rod Carew

“I’m a tough guy, a gambler on horses, a slave driver, and in general, a disgrace to the game. I wish I knew why. I only wanted to win.” - Rogers Hornsby

“Used to be.” - Grover Cleveland Alexander’s answer to a fan’s question whether he was the great baseball player

“They were all against me, but I beat the bastards and left them in a ditch.” - Ty Cobb

Barry Bonds’s teammates at Arizona State voted to kick him off the team.

Willie Mays wore caps a size too large in order to give the crowd a thrill when they flew off.

Fathers & sons

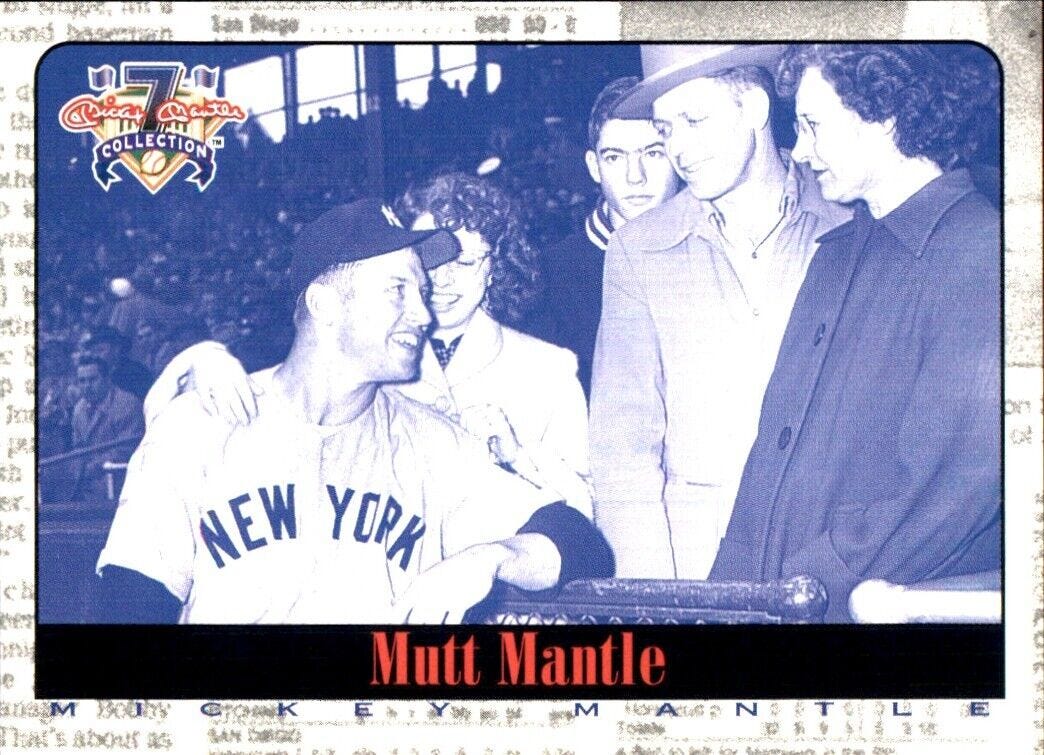

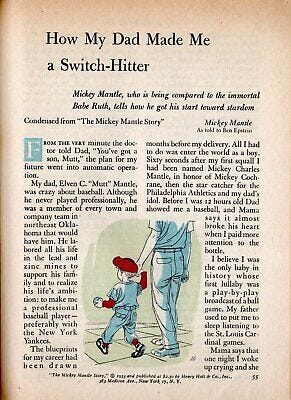

The relationship between fathers and sons is the first key theme of The Baseball 100. The most famous of course is Mutt Mantle, father of Mickey, who set the standard by training his son as a switch hitter and whose approach can be seen in his pep talk when Mickey was having doubts about his abilities: “I thought I raised a man, but I see I raised a coward instead. You can come to Oklahoma and work the mines with me… I didn’t raise a man. I raised a baby.”

That was probably the extreme, but the stories of fathers who trained their sons don’t stop (and there are likely more that Posnanski doesn’t mention). They include:

Nobuyuki Suzuki, who saved his son’s shoes and toys for a future museum

Vince Piazza, who pulled strings with his friend Tommy Lasorda to get Mike into college and drafted (he went in the 62nd round)

Cecil Fisk, whose pressure led to Carlton’s response at his HOF induction: “Just because you could have done better doesn’t mean that you’ve done badly.” And when Cecil was visiting the Red Sox clubhouse, a coach asked, “So, Mr. Fisk, you’re Carlton’s dad, huh?” “No, Carlton is my son.”

Evan Perry, about whom a neighbor said, “All them Perry boys want to do is play baseball and their dad is even worse”

Harry Rose, who promised the little league coach that Pete would play his heart out if allowed to switch hit

Larry Jones, who explicitly adopted the Mutt approach including switch-hitting and the nickname Chipper

Cal Ripken, who taught his kids the Oriole way - back up your teammate, communicate, take pride in fundamentals

Karol Yastrzemski, who dreamed of getting his son the biggest ever contract for an amateur and held out for over 100K

Jack Brett, another admirer of Mutt who made George “scared every single day”; and after George’s .390 season shouted: “Do you mean to tell me you couldn’t have gotten five more !@#$%^ hits?”

William Feller, who built a ballpark for his son, inspiring the book and film Field of Dreams

Edward Spahn, who trained his son to pitch on the theory that left-handed pitchers were always needed

Ted Bench, an Oklahoman like Mutt who saw catching as the best route to the majors

Edwin Matthews, who taught his son to pull the ball in order to avoid hitting mom who pitched to him while dad fielded

Leonard Morgan, who taught his son the importance of versatility

Philip Niekro, who taught Phil the knuckleball and in response to the offer of a $500 signing bonus said, “We don’t have that kind of money”

Jeff Trout, who was a great minor league hitter but gave up the sport when teams refused to promote or release him, though apparently he did not push the game on his son

A few were a different model

Roger Clemens “never wanted for anything except possibly a father in the stands watching me pitch”, though he did admire his stepfather who died when he was eight; his brother Randy was a Reese Bobby clone who taught him that either you win or you fail

Ted Williams barely knew his father and hid the Mexican heritage of his mother

Bob Gibson, whose brother Josh played a father-like role and not only for Bob but also for pro athletes Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, and Johnny Rodgers

And of course there are the greats who were sons of great players like Sandy Alomar, Jr., Ken Griffey, Jr., and Barry Bonds

And finally the most tragic father-son story of them all:

Ty Cobb, whose father was shot dead by his mother while trying to catch her in an act of infidelity; Cobb’s teammates then brutally hazed him about the murder, leading to a nervous breakdown

As Posnanski puts it, quoting the film Searching for Bobby Fischer, “How many ballplayers grow up afraid of losing their father’s love every time they come to the plate? All of them.”

Do other sports have this same father-son connection? My sense is that it is stronger in baseball because it requires more apprenticeship-like skills. Pitching, batting, and fielding all require something more than pure athletic skill and all of them need to be practiced with another person (a friend or parent). Plus, baseball is more of a rural game where family units are more closely knit as opposed to city games like basketball. Whatever the cause, it is these father-son stories that form one emotional heart of the book and of the game.

The most telling combinations of player and quote according to Posnanski

Ernie Banks - It’s a beautiful day, let’s play two (and after a 100 degree doubleheader in Houston - They’re all beautiful days, Buck, just that some days are more beautiful than other)

Lou Gehrig - Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth

Satchel Paige - Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you

John Kruk - I ain’t an athlete, I’m a ballplayer

Garry Templeton - If I ain’t starting, I ain’t departing

Reggie Jackson - I didn’t come to New York to be a star, I brought my star with me

Race and baseball

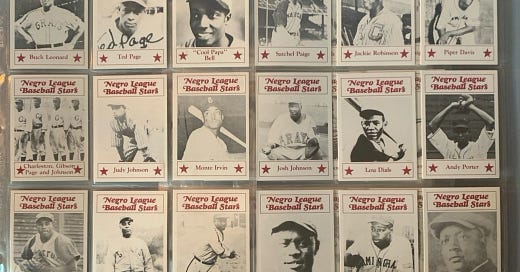

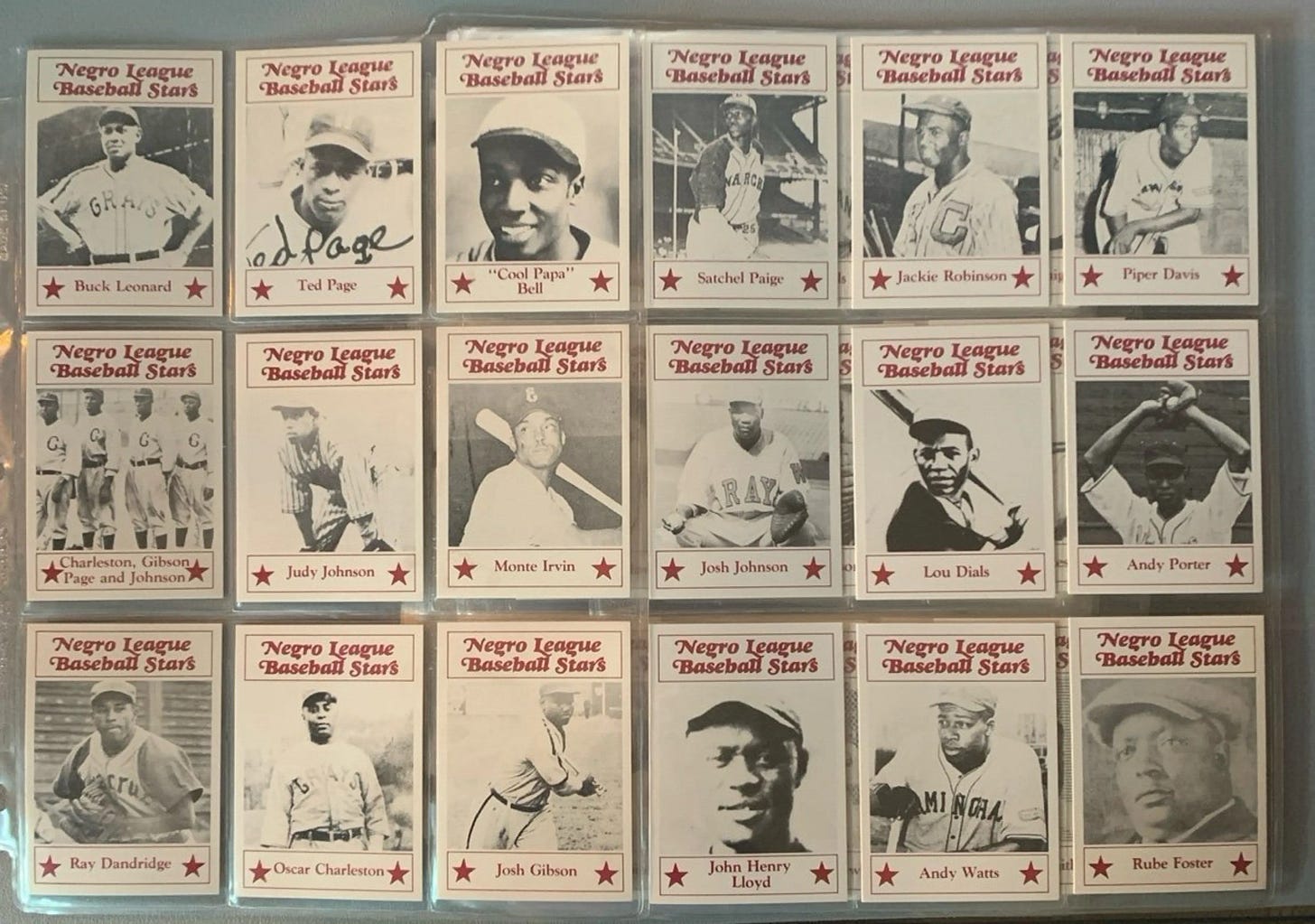

The second emotional heart of Posnanski’s book is race. Some of the most impactful entries concern Negro league players and their successors. As the longtime national pastime, baseball has a deep and inglorious history with race. Posnanski is on firm footing here. He wrote the excellent The Soul of Baseball: A Roadtrip through Buck O’Neil’s America that detailed the life of one Negro League great and has worked closely with the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, his long-time home.

The difficulty of course is getting a real sense of how good were players like Bullet Rogan, Smokey Joe Williams, Buck Leonard, Pop Lloyd, Josh Gibson, and Oscar Charleston (all featured in the book with Charleston coming in at 5th on his list) in the absence of much documentation.

As Posnanski puts it, “If I was one of the few people who got to see Mark McGwire play, how would I tell the story; I couldn’t convince you unless you were willing to believe.” He thus recounts legends galore about the speed, strength, and wiles of these players. Smokey Joe Williams needed two catchers per game because he threw so hard. Satchel Paige intentionally walked a batter in order to face Josh Gibson with the game on the line. And then there are testimonials from all-time greats. I most liked Honus Wagner’s response when told that Pop Lloyd was called the black Honus Wagner (for both his play and his gentlemanliness): “It is a privilege to have been compared with him.”

Posnanski notes how the success of black players in the majors was both contingent and foreordained. Consider Jackie Robinson in 1947: he was 28 years old, had played one season of college baseball, had a bad ankle, and was almost court-martialed out of the army. As Posnanski puts it, “what would social media say today about the Dodgers signing a former football, basketball, and track star who had some success with a war-depleted barnstorming baseball team?”1 And by the end of 1947, there had been five black players in the league and only Robinson could be considered a success. Pitching was a minefield with Dan Bankhead afraid to pitch inside because he worried that if he hit a batter he would cause a riot.

On the other hand, the pipeline of talent was enormous. One or more all-time greats entered the league every year after 1947 - Doby, Campanella, Minoso, Newcombe, Irvin, Mays, Banks, Aaron, and Clemente. Mobile, Alabama by itself produced Hank Aaron, Billy Williams, and Willie McCovey within a couple of years of each other. Move Robinson’s entry just a few years into the future and MLB loses the prime of its greatest stars, including the #1 on Posnanski’s list, Willie Mays. Move it into the past and you can imagine what it did miss.

The reactions to missing out might be the most fascinating. Robinson’s toughness and suppressed anger are well-known, at least partially because of Roger Kahn’s sympathetic portrayal in The Boys of Summer. Monte Irvin likewise couldn’t let the injustice go. He was voted by Negro League owners as the right player to break the color line back in 1942, but didn’t join the league until he was 30. (At least one reason was that Branch Rickey refused to pay any compensation to a Negro League owner for his contract - neither to Irvin’s Newark Eagles nor to Robinson’s Kansas City Monarchs.) Mentoring a young Willie Mays, Irvin said, “You remind me of me.” It is hard not to sympathize with what was taken from them.

But then there is Roy Campanella who refuses “to admit that any phase of his life was especially difficult or unpleasant.” Pop Lloyd didn’t think he was born too early: “Because many of us did our best for the game, we’ve given the Negro a greater opportunity.” Or Buck O’Neil: “The people I feel sorry for were the ones who didn’t see us play.” Rather than regret not batting against Bob Feller, he feels joy that he faced Satchel Paige in his prime. What is the right way to feel? It’s not for me to say.

The story of baseball and race is at once tragic and hopeful. Too much was lost and can never be recovered (as opposed to say jazz where performances lived on through others). But it gave us in Jackie Robinson a national hero who stood on the shoulders of giants.2

A few trivia questions (answers below)

Which childhood friend of Phil Niekro later became a Hall of Famer for the Boston Celtics?

Who were the only two players who struck out their age in a major league game?

Who has the all-time Milwaukee Braves HR record?

Who played more games than any other American Leaguer?

Which Hall of Fame catcher was Leo Durocher referring to when he said that nice guys finish last?

What Hall of Famer was named after TV star and singer Ricky Nelson?

Who won the first MVP award?

What Hall of Famer was the first African American to manage a major league game?

Who is the only Canadian pitcher in the Hall of Fame?

The largest crowd in baseball history (until 2008) attended an exhibition game at LA Coliseum to honor which injured player?

What two players have the all-time HR record by teammates?

Who is the first player to have his number retired?

Who is the lowest draft pick to make the Hall of Fame?

Which two all-time great left-handed hitters were born in Donara, Pennsylvania (current population 4,558)?

Answers:

John Havlicek

Bob Feller (17) & Kerry Woods (20)

Eddie Matthews

Carl Yastrzemski

Mel Ott

Rickey Henderson

Lefty Grove

Frank Robinson

Fergie Jenkins

Roy Campanella

Eddie Matthews & Hank Aaron

Lou Gehrig

Mike Piazza (62nd round)

Stan Musial and Ken Griffey, Jr.

Evaluating talent

A third main theme is how we evaluate greatness. Though Posnanski’s book is explicitly about the greatest players, some of them were underrated in their day and sometimes even today. This obviously applies to all of the Negro League players who I discussed above. But I was curious why others are underrated despite being among the greatest. I saw a few reasons.

Numbers & awards

Not winning (enough) key awards or meeting key round numbers is a key factor. Those who bear this burden include Mike Mussina (several almost Cy Youngs and almost no-hitters), Robin Roberts (no Cy Youngs, the award was introduced after and because of his best seasons), Bert Blyleven (20 wins only once, no Cy Youngs), and Lefty Grove (an ERA of 3.06, that is, over the magical 3.00, though he sometimes led the league and played in extreme hitters’ parks; Grove also languished in the minors for years when he was arguably the best pitcher in the world). Perhaps Joe Morgan would fall here as his excellence was only revealed by advanced statistics. Ironically, “Morgan the announcer didn’t understand what made Morgan the player so good.” Sometimes the problem was playing in the wrong era. Pitchers suffered in the hitter’s era of the 1930s and 1950s (see Grove and Roberts), while hitters suffered in the pitcher’s era of the 1960s (see McCovey or Yaz, though both still put up impressive numbers).

Personality

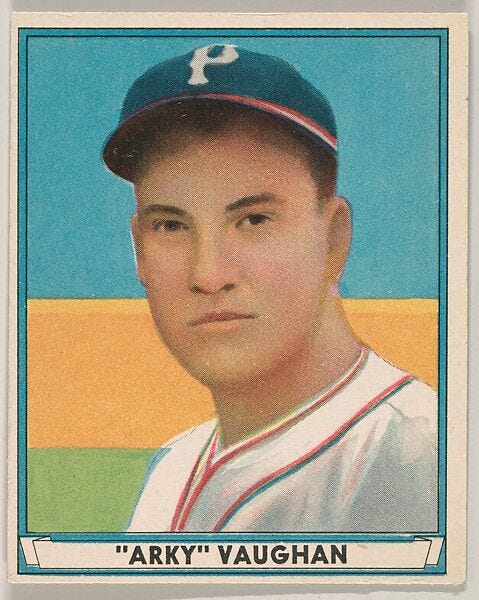

Players with smaller or conflictual personalities tend to be underrated. Again, Mussina was unwilling to make the case for his own greatness (Coopers-Frown wrote The Daily News on his retirement). Robin Yount meanwhile seemed not to like baseball and even threatened to become a pro golfer (he won 2 MVPs but was named to only 3 All-Star teams). Posnanski calls Arky Vaughan the least known great player partially for being quiet and modest (he clashed with his two aggro managers - Frankie Frisch and Leo Durocher - who both enjoyed playing head games with players) and also for playing for mediocre teams. Eddie Matthews meanwhile ran hot, but clashed with sportswriters who later penalized him in Hall of Fame voting. Mike Trout on the other hand is simply viewed as boring. Is it revealing that I usually prefer the quieter players? My favorites growing up were Ron Guidry and Don Mattingly.

Lack of famous moments

In his entry on Larry Walker, Posnanski writes that “people who do famous things tend to be overrated and people who are good day after day are underrated.” Others penalized in this way might include Carlos Beltram who played his early seasons for bad teams and struck out in his biggest playoff moment. Or Johnny Mize who is remembered for his last years as a part-timer on the Yankees instead of his dominant years on a fading Cardinals team. Those who languished on bad teams belong here as well, say, Fergie Jenkins or Robin Roberts (though not Ernie Banks).

Typecasting

Several players were underrated because they were typecast as a certain kind of player or for a certain role. Wade Boggs may be the most tragic case. He remained in the minors for years (he competed for five! minor league batting titles) because as a third baseman he was supposed to hit for power. A student of Ted Williams, he refused to go after bad pitches in a quest for HRs. Frank Thomas was another Williams disciple whose perfectionism at the plate was ignored because of his massive size and power. Though not exactly underrated, Hank Aaron’s incredible HR totals similarly overshadowed how good a hitter (3,000 hits even subtracting his HRs), fielder, and baserunner he was.

For me the even more interesting case is Bob Gibson. He might be best remembered for the way he intimidated hitters. As Posnanski notes, how many players have two classic stories of plunking a batter in an old-timer’s game? But what was forgotten was how hard he worked at his craft, how well he fielded, and how good a hitter he was. As Gibson said, they treated him like a bully, but bullies can’t win games: “Did anyone say Tom Seaver won games because he was mean?” Race probably played a role here too.

A few pieces of wisdom from Posnanski

“So much in life is a matter of style” - In reference to the way that Nap Lajoie and Ty Cobb were both legendary for their rough play and hard lifestyles (Lajoie spiked three players in an inning and played drunk), but Cobb became baseball’s main villain and Lajoie was beloved because he was “so friendly and fun-loving”. Also in reference to the way that fans hate some cheaters like Bonds and Clemens and love others like Gaylord Perry who seem to take pleasure in getting away with something.

“Sometimes magic is just spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect” - In reference to the way that Greg Maddux would inordinately study every hitter and at-bat to find ways to steal extra strikes.

“People aren’t one thing” - Buck O’Neil. Quoted in reference to the way that Tris Speaker was a racist and a member of the KKK, but later enjoyed working with Larry Doby. Even Ty Cobb mellowed in his old age.

Money

Though not a major theme, Posnanski’s book is replete with stories of players being underpaid and fighting for more money by not signing the contract they were proffered. They almost all end in the same way. The press (always ready to support ownership) and fans turn against the player who humbly returns to the team. Posnanski mentions this explicitly in the entries on Greenberg, Carlton, Koufax, Kaline, Berra (a reason why many of his quotes are about money), DiMaggio, and Ruth. Presumably their failures deterred lesser players from even putting up a fight.

I have always been intrigued by the psychology here. Why do fans so often turn against players in these negotiations? In what other situations do we side with the millionaires against their employees? One can see it even for players that are successful in getting paid like Alex Rodriguez. Is there a deeper point about human nature lurking here? Do we envy the players (workers like us) more than the owners?

If you only have time to skim a few entries before deciding whether to read the book, I’d recommend the following:

Phil Niekro and how he didn’t throw a knuckleball in his 300th win

Carlton Fisk and his relationship with his father Cecil

Bob Feller as the inspiration for both The Natural and Field of Dreams and president of the “In my day, ballplayers were ballplayers” conglomerate

Bob Gibson and his reputation (see above)

Grover Cleveland Alexander and his sad end

Ty Cobb and his demons

Conclusion

I suppose I should conclude with some thoughts about what happened to baseball - why I love the sport’s history and this book but don’t follow the current game. The standard explanations are that it is too slow for current attention spans - both the play on the field and the 162-game season. I suppose that applies to me, but the time commitment has led me to watch less of all sports, including my favorite, basketball. Possibly those other sports lose less when compacted into highlight videos; I think baseball suffers more when you see just the outcome of at bats.

I might instead point to Tyler Cowen’s motto: “Context is that which is scarce”. At some point, I lost my context for baseball. I fell out of touch with teams and trends. Maybe while living abroad. I also lost fandom - for various reasons the Yankees and Mets didn’t seem worth rooting for and I was an interloper for the Cubs and White Sox where I lived. There were too many players and teams to get to know and not enough continuity of dominant teams and player/team connections to make it easier. In short, the context was gone and it wasn’t easy to recover.

And baseball arguably is the most context-dependent of our major sports. The game lives in the shadow of Babe Ruth and those who chased his records suffered for it (Greenberg, Foxx, Mantle, Maris, Aaron). Even Rose’s chase of Cobb was fraught as were Brett and Carew’s pursuits of .400 or any hitting streak. The sport makes much sense with this background. The thing I appreciate about Posnanski is that he continually keeps the big picture in mind even while highlighting the details and stories. Maybe he has given me enough context to start watching again.

An irony is that Robinson’s playing style was one of the few to resemble that of notorious racist Ty Cobb.

It is interesting to see his mentions of other ethnicities. John McGraw, the famous manager of the Giants, said that he would give a hundred thousand dollars for a Jewish player who had even the prospect of being a real star, though he somehow passed on Hank Greenberg. Meanwhile in Japan, Sadaharu Oh was overshadowed by Shigeo Nagashima because his father was Chinese. There is a bit less on the Latin experience, though Posnanski does trace the evolution of pitchers from the Dominican Republic, the Road to Pedro (Martinez, that is).