For some reason there are relatively few histories of political science. I can think of good books about the evolution of economics, sociology, psychology, and even anthropology, but for political science I only know a couple of edited volumes. (Tell me if I’m missing something.)

I can think of a few reasons why:

Other fields are united by a method and approach going back to their founders, while political science is united by a topic and has less of a founding figure or moment. I’ve discussed this in some previous posts.

Political science tends to import trends from other fields and thus has less of its own history. Again, I’ve written a little on this.

Political science is more divided than other fields and thus does not have a single history. (Yes, anthropology is arguably even more divided, but histories of anthropology tend to focus on the cultural subfield.)

To serve as a partial remedy for the absence of good histories, I decided to test a few hypotheses about the evolution of political science. I did this by searching the texts of political science books in the HathiTrust Digital Library.1 I began with the standard history of the field that we tell ourselves. I then turned to some common criticisms of the field and particularly areas that we purportedly neglect. Finally, I considered how much major events drive attention.

Here are the key takeaways:

I found confirmation for some of the standard history, particularly the behavioral revolution, the expansion to the developing world, imports from other fields, the rise of identity politics, and increasing attention to methods, but with surprises on the (non-)replacement of cultural by rational approaches and the (non-)rise of institutional analysis.

Several of the criticisms of the field, however, are at least partially unfounded as political scientists continued writing about many of the areas that they purportedly neglected such as power, bureaucracy, local politics, and leaders (of course, word frequencies do not capture changes in how these things are studied).

There is some evidence that we respond to trends in real-life politics like democratization and globalization, but not always. For example, trends in mentions of nationalism, genocide, and terrorism don’t seem to correspond to real-world events and there is some ambiguity with war and communism.

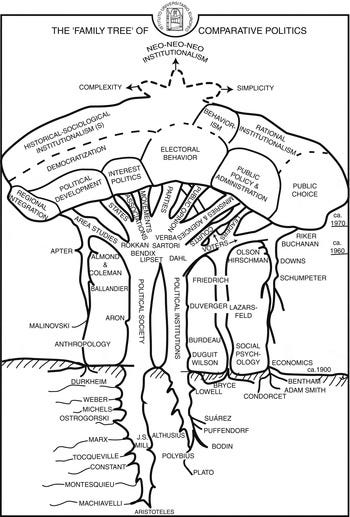

The history of political science

The standard story of political science is that it began with legalistic analyses of political institutions in the early 20th c. and was then reinvented by the behavioral revolution and the turn to the developing world starting in the 1950s. From there, diverse movements emerged: rational choice in the 1960s, the new institutionalism in the 1980s, more methodological rigor in the 1990s, and identity politics perhaps in the 2000s though also going back to the 1960s. Throughout this time, political science has been an importer from other fields - sociology, economics, and psychology at different times. How much can we see these trends in texts?

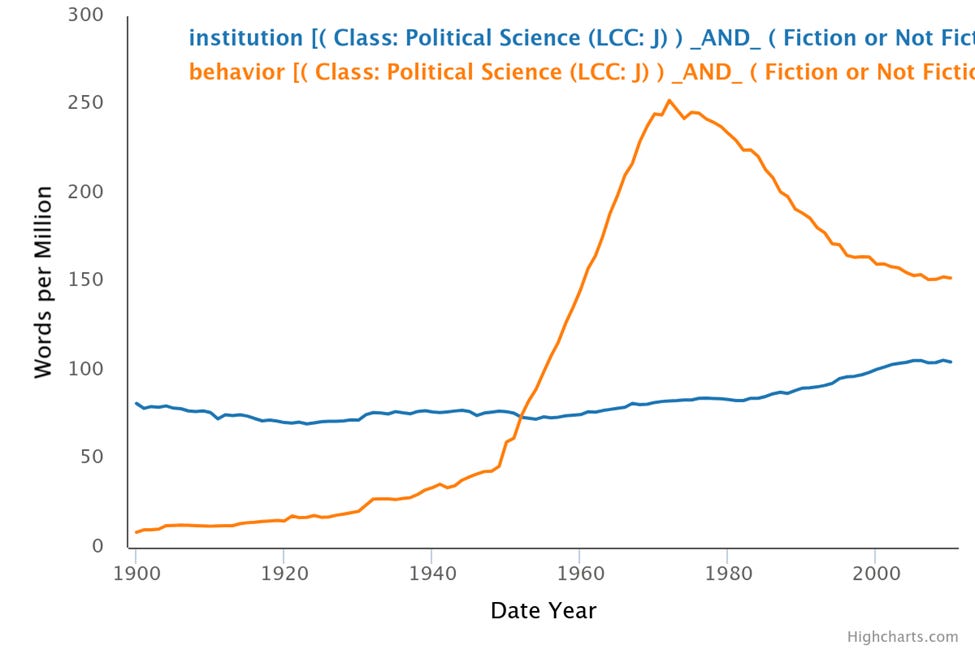

The behavioral and institutional revolutions

The behavioral revolution shows up very clearly in the data with an enormous jump in the use of the word ‘behavior’ from around 1950 to 1970. After that it declines perhaps because of overuse, taken for grantedness, or competition from other approaches. ‘Institutions’, by contrast, are a steadier part of the field though at a lower level with possibly a gradual increase from the 1970s. (FN: This might confirm Almond’s claim that institutions didn’t have to be “brought back in”; they were always there.)

Institutionalism, however, has been better at marketing with the word ‘institutionalism’ taking off in the 1980s, though note the far lower levels than in the first graph. ‘Behavioralism’ saw a rise during its heyday but at a lower level. Did they refer to themselves in other ways? Or were they so dominant that using a label was unnecessary?

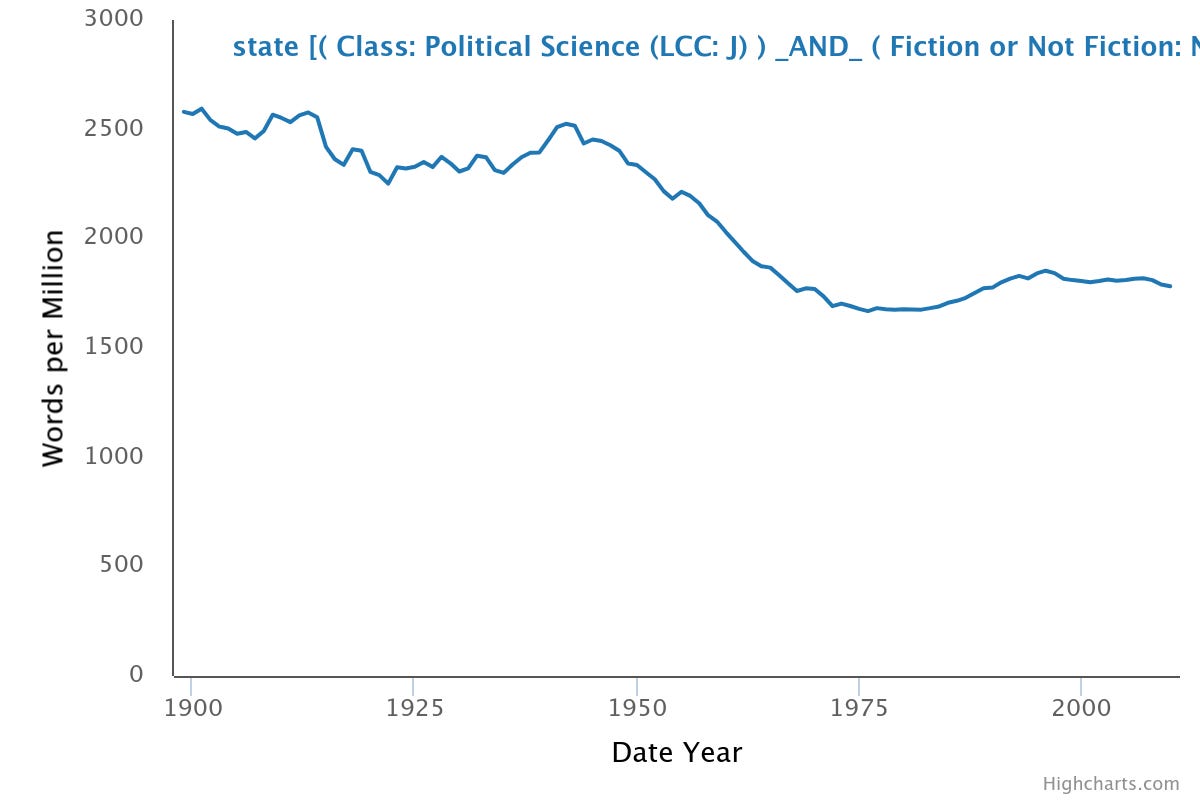

As an addition to institutions, I checked ‘state’. Surprisingly, the term ‘state’ has actually declined even as it was “brought back in”. Of course, in the case of institutions and the state, the innovation may be the way these concepts were being used which is harder to track with single-word searches.

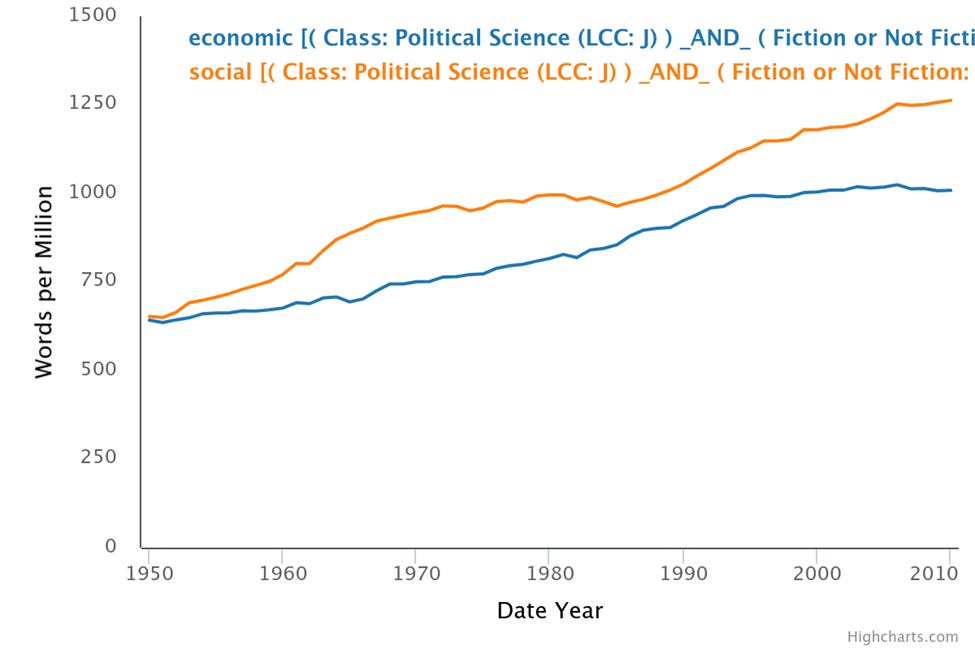

Imports from other fields

As I pointed out elsewhere, political science is seen as an importer from other fields, particularly sociology and economics. The graph below shows a consistent increase in use of the terms ‘economic’ and ‘social’ with social factors having a slight edge over economic, though of course not all mentions are imports. Both are used at very high levels and ‘political’ (not shown) is even higher. I had included ‘psychological’, but it appears much less frequently.

Alternatively, I tried looking for the capitalized versions of Economics, Sociology, and Psychology to get a sense of references to those fields (all of the other searches are case-insensitive). Economics leads this race, especially recently, but this may be because it can refer to a topic as much as a discipline. Psychology performs better with this approach.

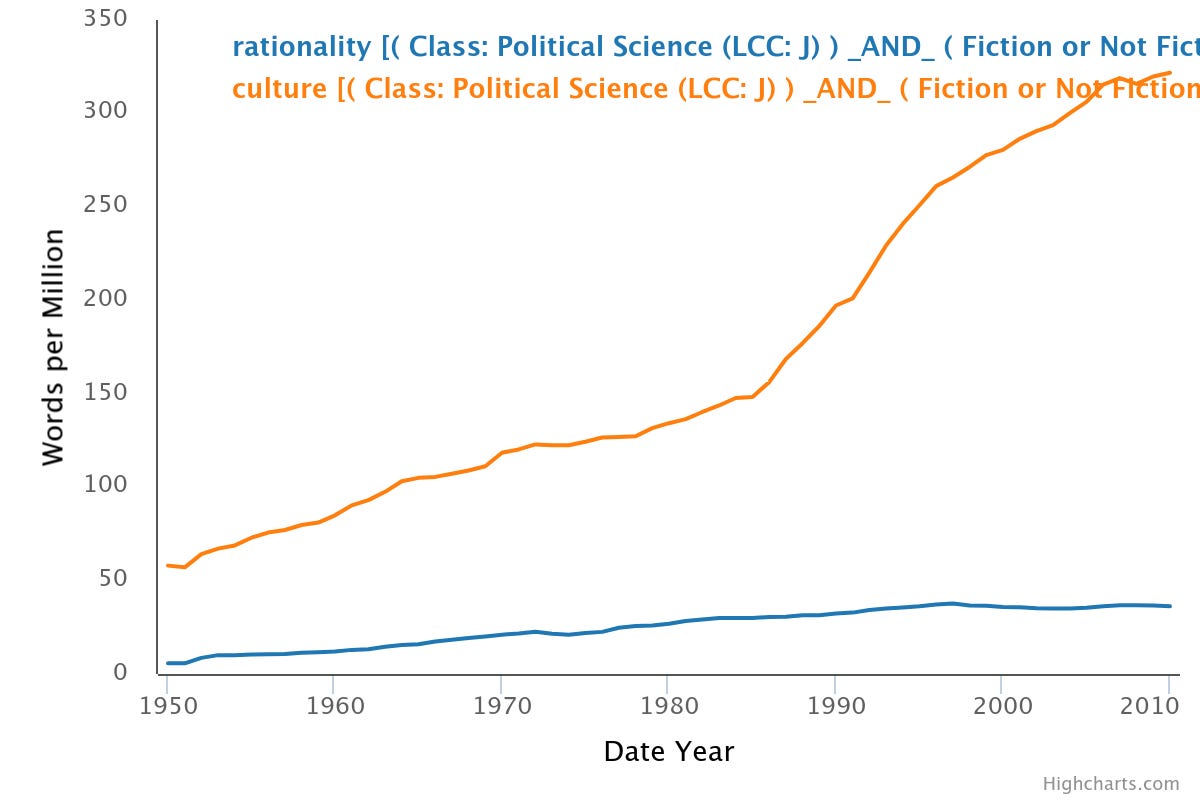

Rational choice versus culture

I thought I might see strong evidence that approaches using rational choice would take off, while those connected with culture would decline. Surprisingly, ‘culture’/’cultural’ was used much more and even grew substantially in the 1990s. Are political scientists using it in ways that I haven’t noticed? (I doubt we are importing from anthropology.) ‘Rationality’/’rational’ increases consistently but at a much lower level and rate. What am I missing here?

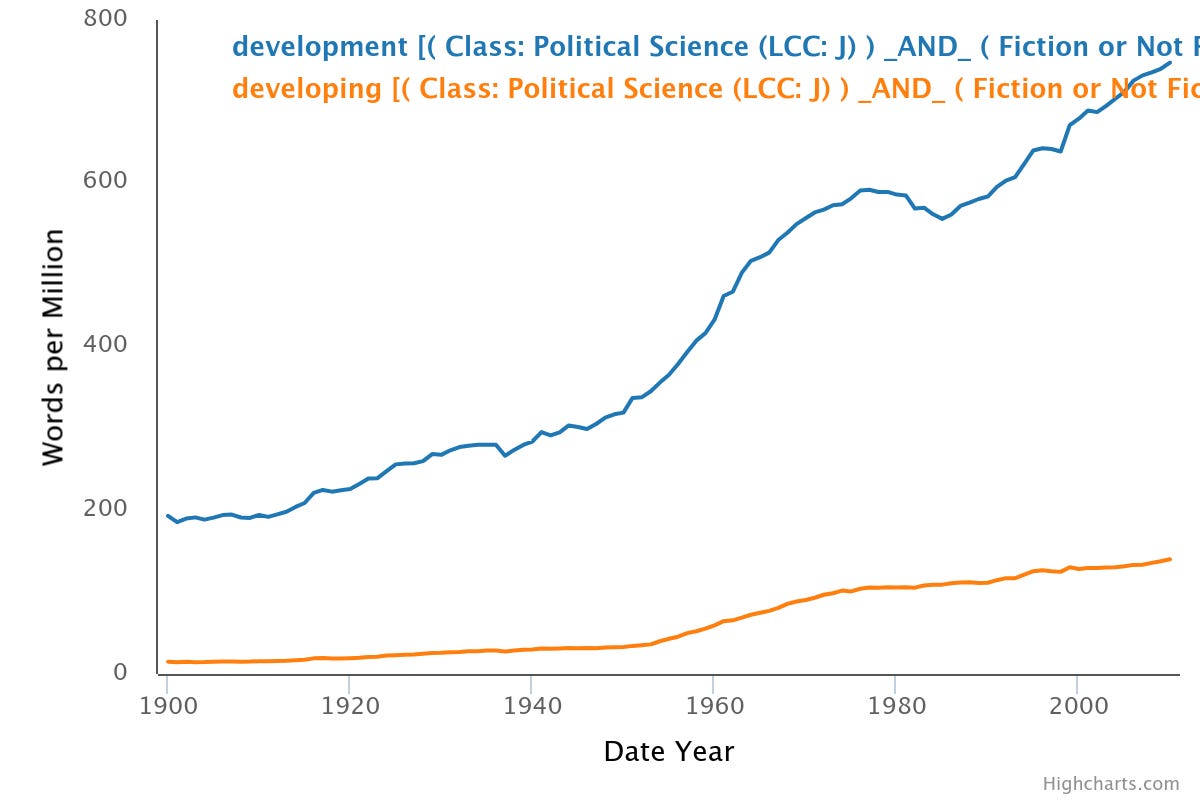

Developing world

One can see some evidence of more attention to the so-called developing world in the postwar era. The words ‘development’ and ‘developing’ both show a sharp upward trend, a four to fivefold increase over a century, with ‘development’ occurring at a very high level, though I can’t be sure that all of these studies use the word in the sense of economic and social change.

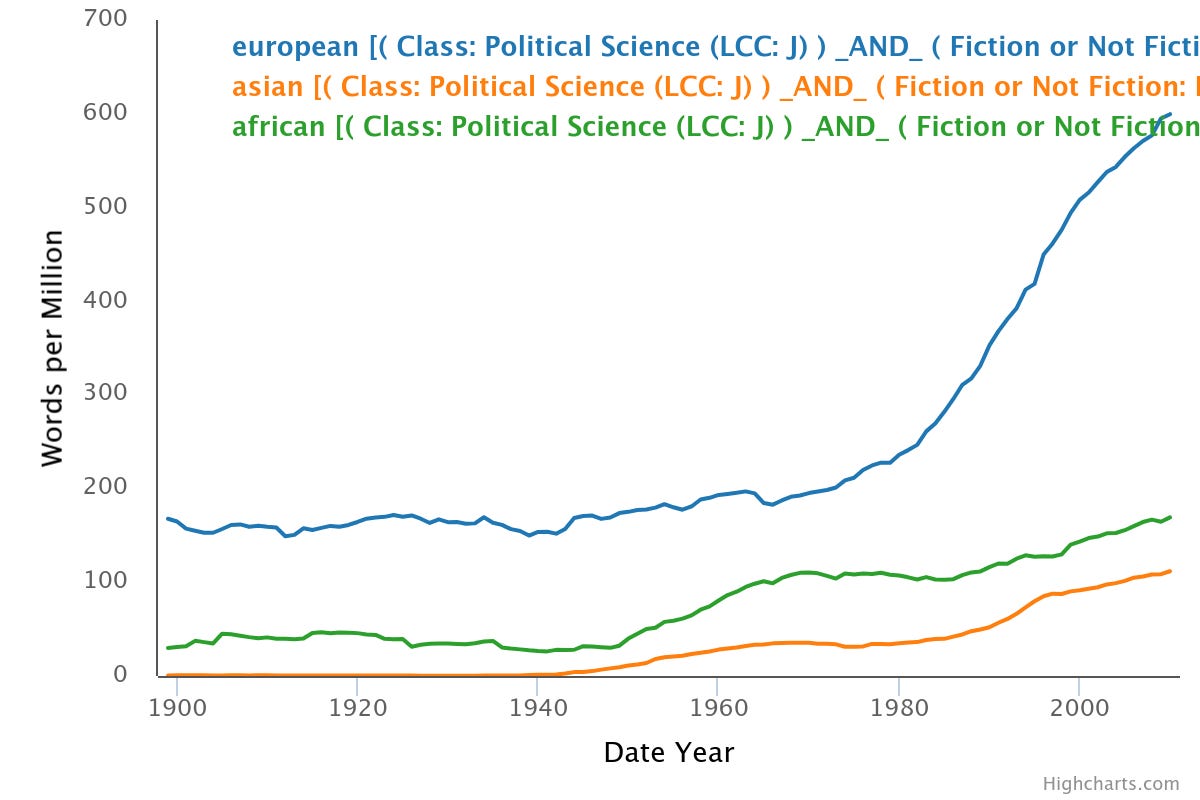

Looking at references to Africa and Asia (Latin America is difficult to capture with one word), we see increases for both regions in the postwar period, but Europe leads both of them with relatively little catch-up. Surprisingly, references to Africa exceed those to Asia, though this may be due to Asia’s political diversity (that is, it is less likely to be seen as a single unit). In the final section, I look separately at China’s rise.

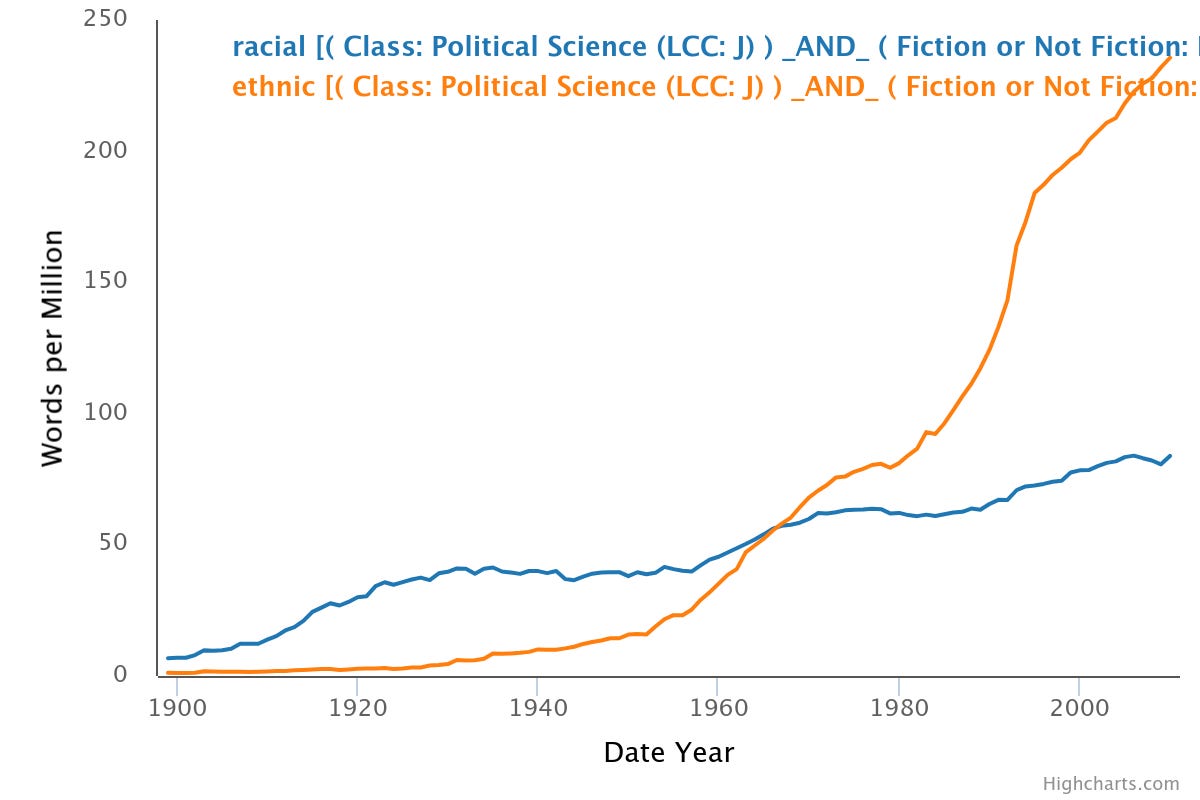

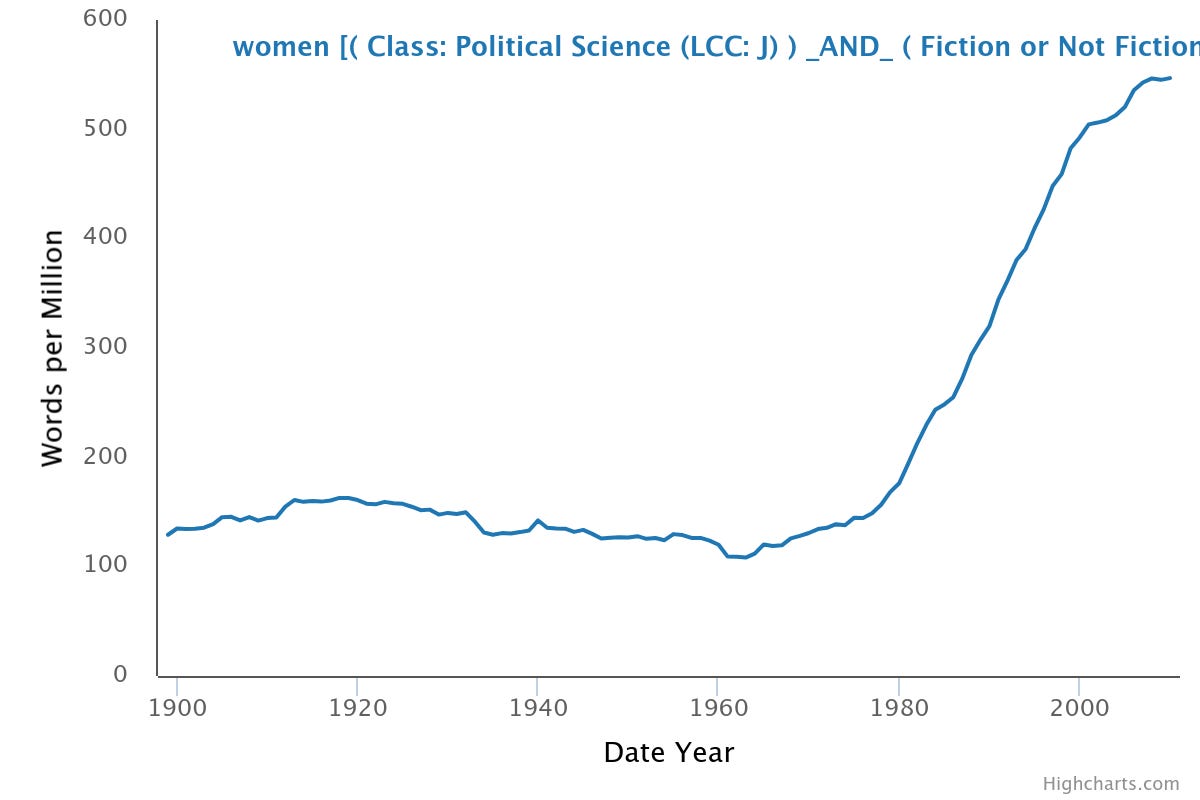

Identity politics

The increase in the mention of identities is relatively clear, though somewhat dependent on search terms. References to ‘race’/’racial’ and ‘ethnicity’/’ethnic’ both start rising in the 1960s (though the word race was prominent going back to 1900). The jump in ‘gender’ (along with ‘female’ and ‘women’) comes later, beginning in the 1980s but then rising precipitously. In raw numbers ‘ethnic’ is the leader today.

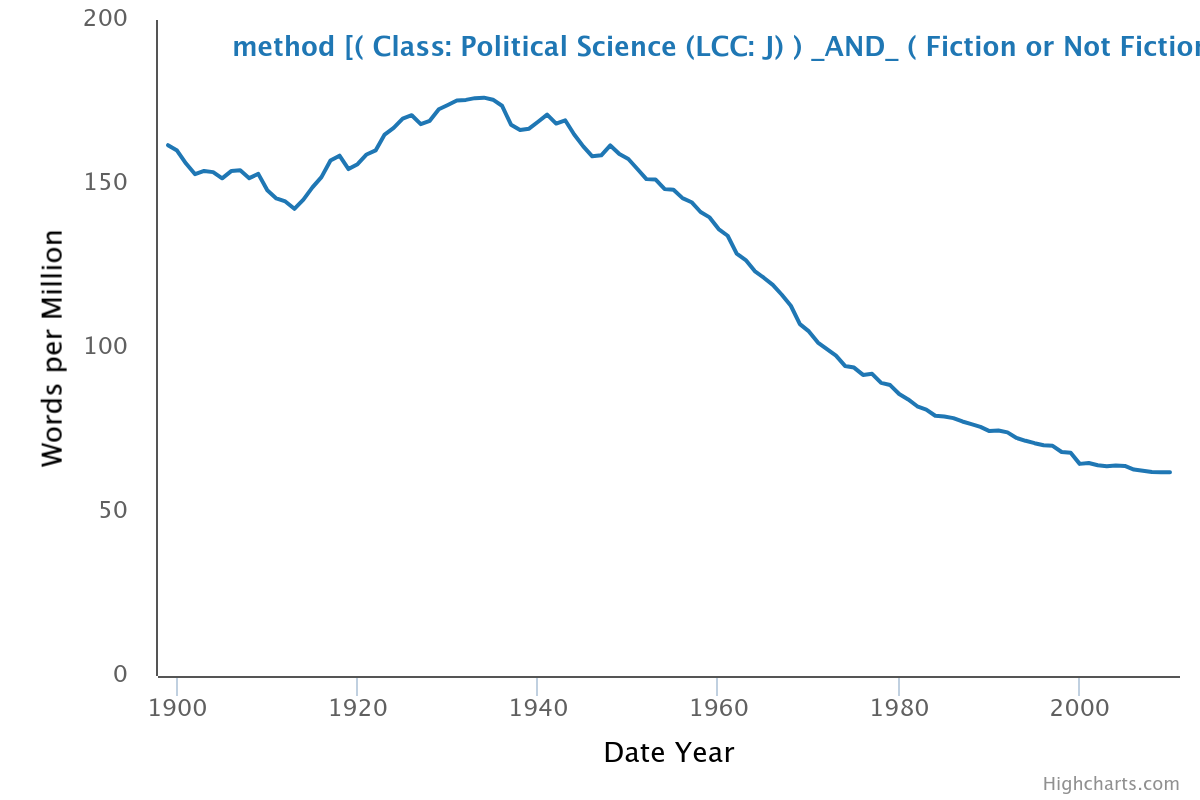

Methods

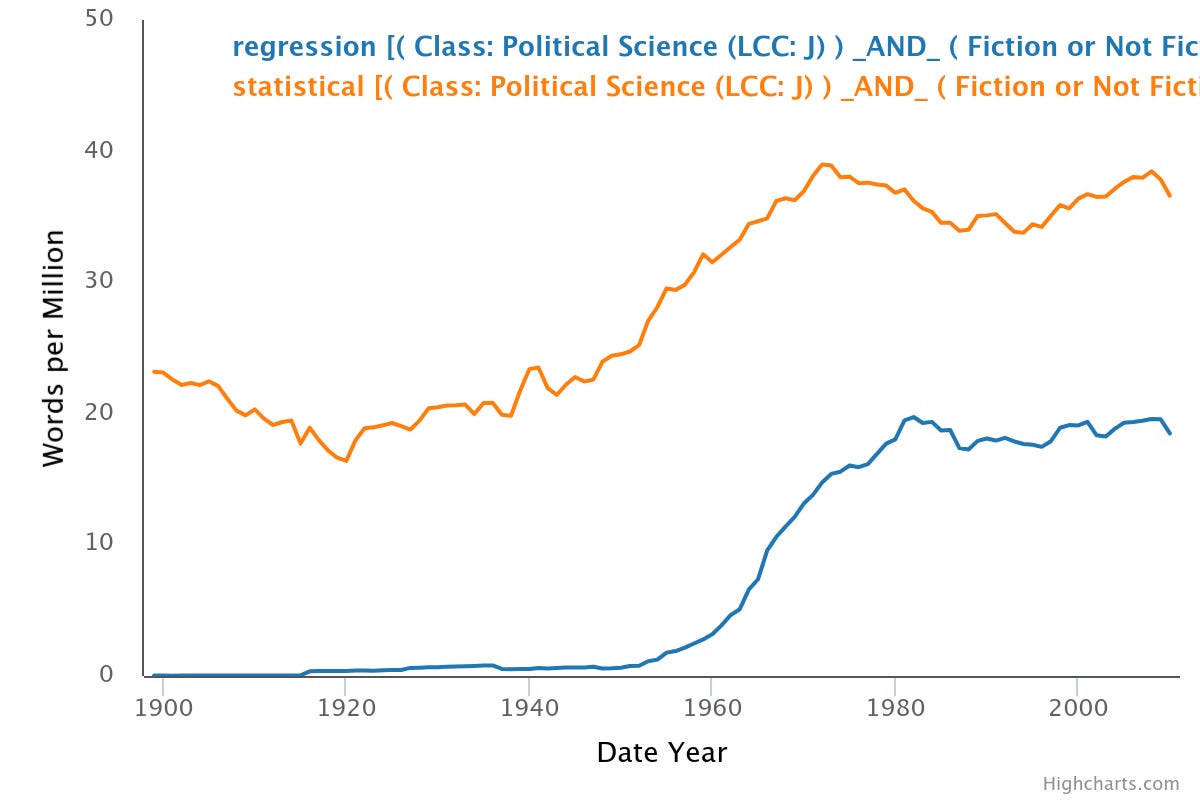

Arguably the largest changes in political science have been the increasing self-consciousness about and rigor of our methods. An analysis of texts provides contradictory results about this. On the one hand, the word ‘method’ appears less in books; perhaps it was used in a more philosophical sense in the past. On the other hand, ‘methodology’ and ‘methodological’ definitely show an upward trend, though at a lower level. These latter trends seem to correspond with the behavioral revolution.

We can see similar increases in both the terms ‘quantitative’ and ‘qualitative’ which are today used about equally, but less for ‘statistical’ and ‘regression’. ‘Statistical’ references have been rising since the 1920s with a plateau in the 1970s, while ‘regression’ only boomed in the 1960s and 1970s and plateaued in the 1980s.

Criticisms of political science

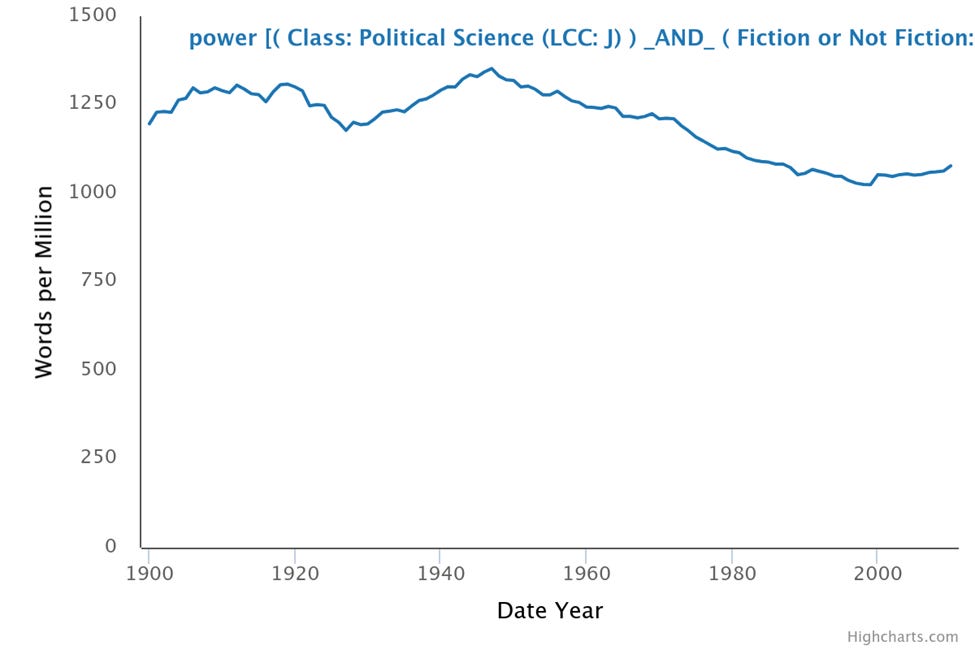

Next, I address some standard criticisms of how the field has evolved. Typically, critics point to areas that have become unjustly neglected. These supposed areas of neglect include a move away from studying power, administration/ bureaucracy, public policy, local politics, and leaders. In most cases, it was hard to spot these negative trends with the prevalence of words.

Power

Munck and Snyder’s interviews with eminent political scientists frequently saw them decry political science’s neglect of power relative to its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s. Contrary to this criticism, the word ‘power’ has one of the highest word counts/million of all the search terms with only a slight decline in the postwar period. One could of course still criticize political science for not doing the right kind of work on power or not making innovations, but scholars were discussing it. I also checked the word influence which was relatively stable at a lower level.

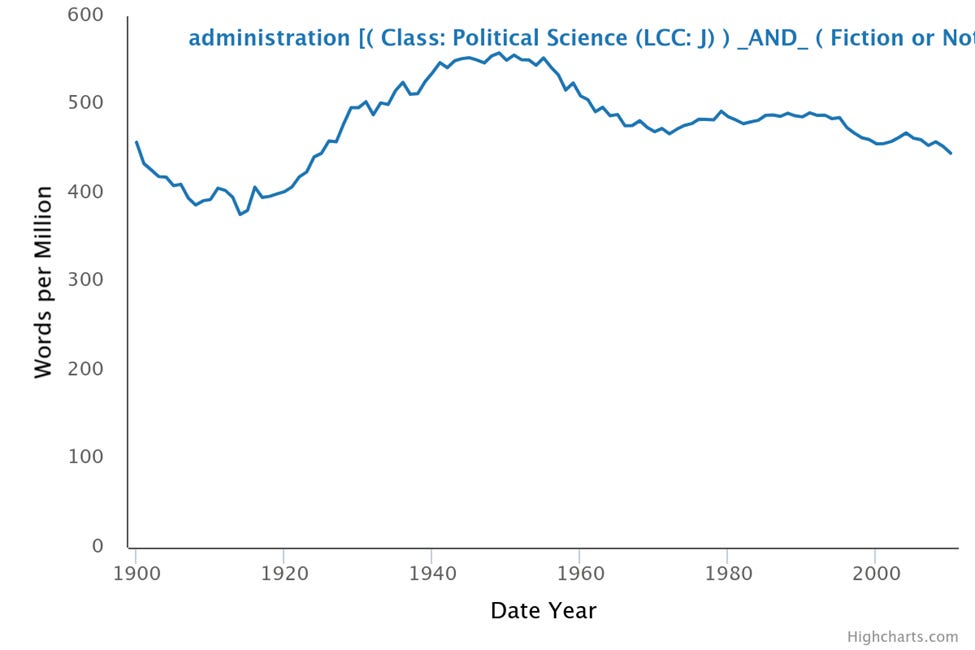

Administration and bureaucracy

I was fairly confident that work on administration and bureaucracy had declined in the field, but use of the word ‘administration’ remains high and ‘bureaucracy’ saw a considerable increase in the 1960s that has mostly held up. Possibly I am just blind to the places where this work is happening.

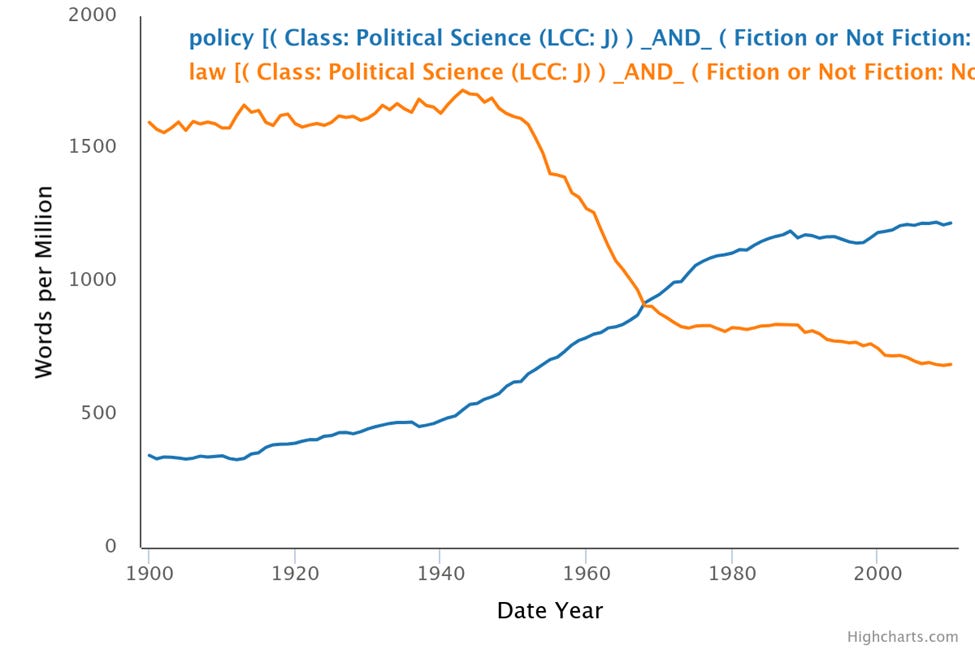

Law and policy

As the field left behind its legalistic origins, it may have also left behind its concern with law and policy. One can see the decline in the use of ‘law’ in the immediate postwar period, but surprisingly there was also an increase in the use of ‘policy’. Maybe this is a specialization and division of labor story where law was hived off into law schools. Or maybe we just began to refer to laws as public policies. This latter possibility strikes me as more plausible. Both of course are used at high levels. There was also a decline in use of ‘regulation’ (not shown) though at a far lower level.

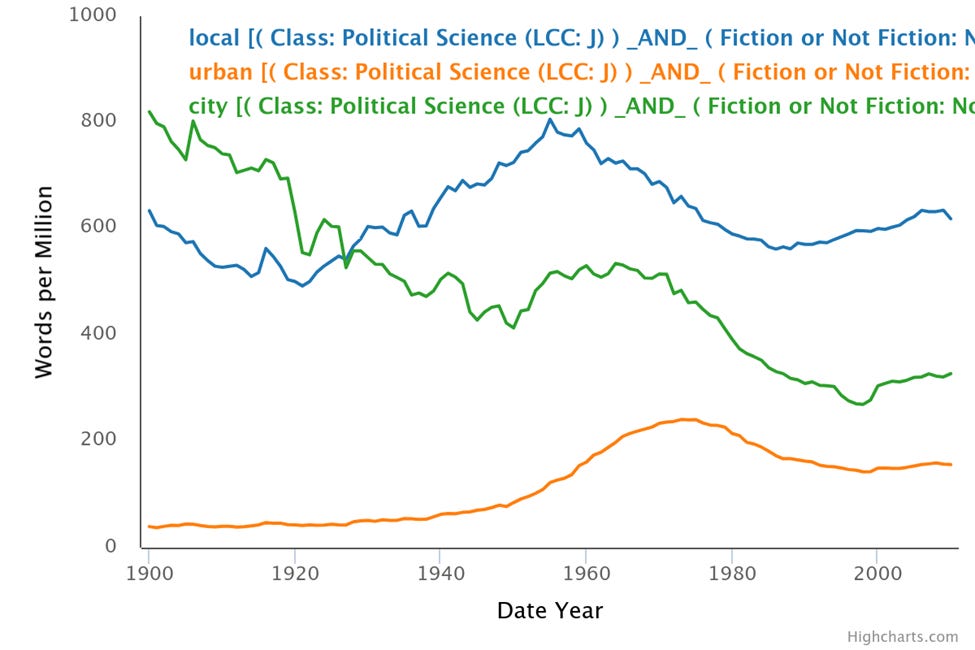

Local politics

Despite worries about a decline in the study of local politics, references to ‘local’ and ‘city’ show relatively high overall levels. ‘City’ has seen a large decline over the past century, but ‘local’ saw a bump in the 1950s and 1960s that then plateaued. ‘Urban’ likewise had a boom in the 1960s and 1970s which also plateaued. The absolute numbers are relatively high for all of these.

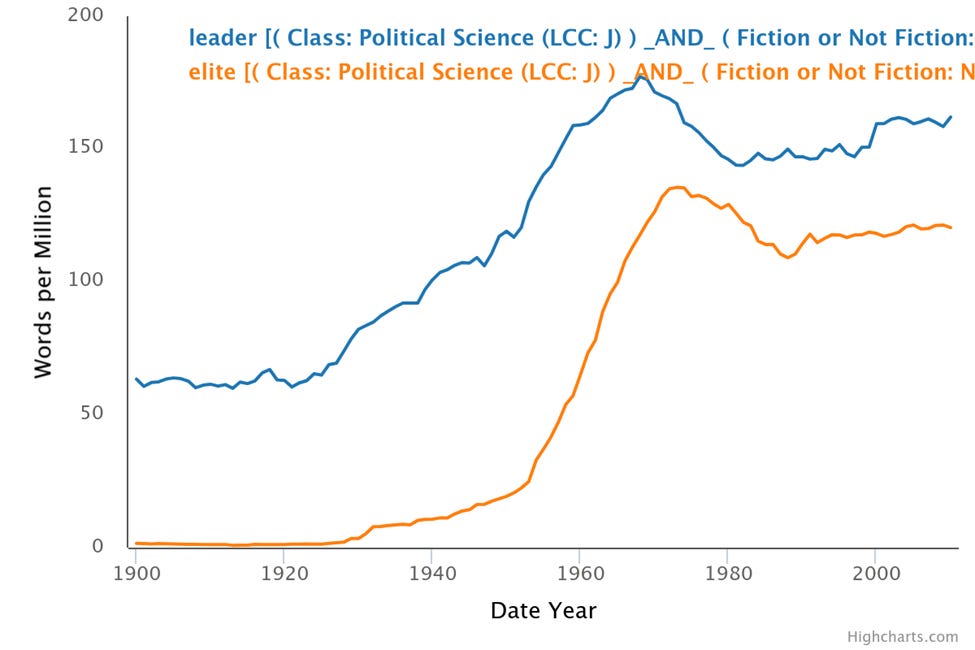

Leaders

I was fairly confident that political science had for a long time not done a great job in studying leaders until a recent resurgence. So how to make sense of the graphs that show precipitous increases in references to ‘leader’ or ‘elite’ during the postwar era until 1970 when there was a moderate plateauing? Perhaps this is a question of prestige and prominence. Books were presumably being written on the subject (indeed, they tend to be among the most popular among laypeople), but they may not have been gaining the attention of the profession.

Responses to events

To what extent does political science respond to events? Can we see this in texts? A few areas where I thought that we might see movements were waves of democracy, the impact of wars, the fall of communism, and the rise of terrorism, globalization, inequality, and China. (I considered Marxist terminology in a separate post here: https://andrewroberts.substack.com/p/the-afterlife-of-communism-redux.)

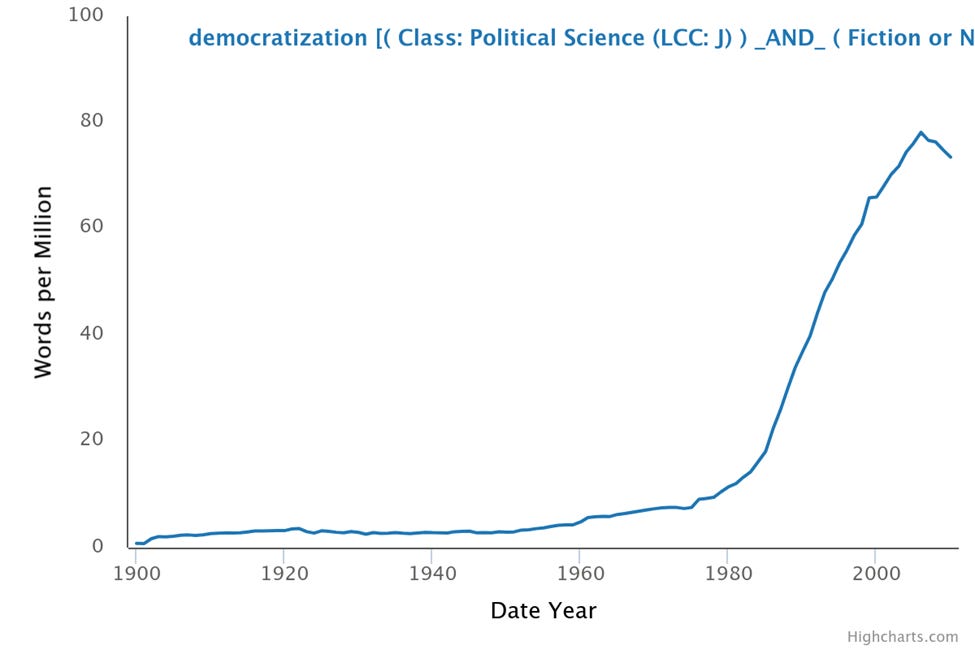

The Third Wave

Democracy shows the most confirmation for our responsiveness to events. References to ‘democracy’ and ‘democratization’ follow a hockey stick curve with the rapid increase dating to the 1980s. This seems like a clear response to the so-called Third Wave. With a little squinting one can possibly see an earlier wave (the second wave?) in the 1930s(!) and 1940s though more for democracy than democratization. Maybe it was a rally-round-the-flag effect.

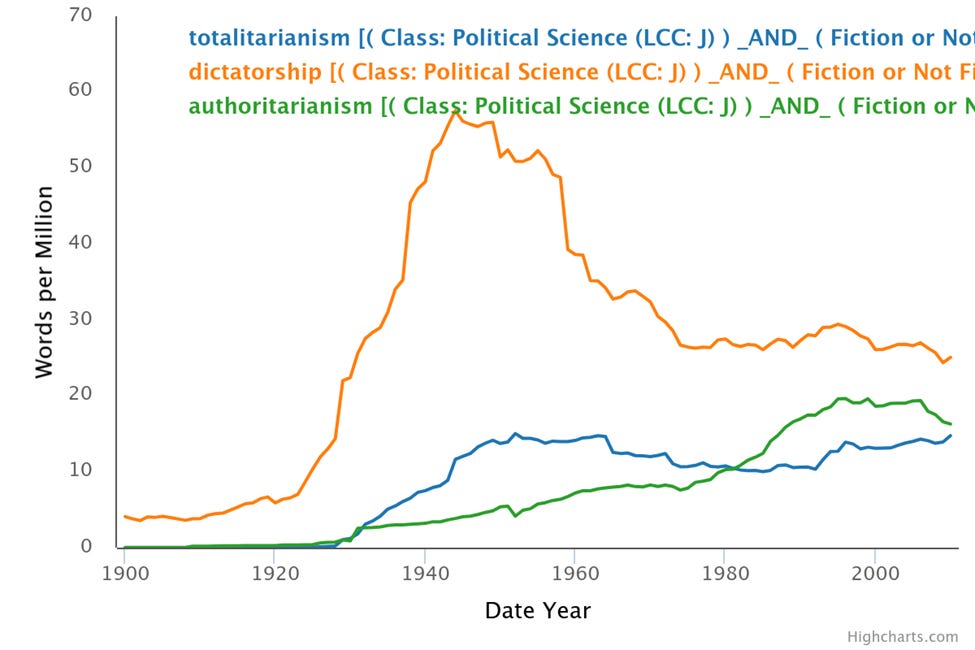

In the study of non-democracies, ‘dictatorship’ shows the strongest trend with a massive spike in the middle of the century, presumably focused on communist and fascist dictatorships. Even with a decline it remains the preferred term. After emerging in the 1930s, ‘totalitarianism’ has surprisingly survived the regimes that inspired it (perhaps more modeling would show what regimes it was connected to). ‘Authoritarianism’ meanwhile has steadily increased, possibly as a neutral term. These numbers are all lower than for democracy, another indication of the profession’s concerns.

Wars and conflicts

Overall, ‘war’ is mentioned at a high level; it rose through the first half of the twentieth century, culminating in World War II. That interest declined and it is hard to see the effects of any subsequent wars. We now use the term at a similar level that we did in 1900, which one could take as a positive or negative sign. We can see a more monotonic upward trend for ‘conflict’ which may have replaced some (but not all) of the references to war.

Nationalism

References to ‘nationalism’ show an interesting bimodal pattern. The first spike is surely connected with real world events, though I would guess that the second one is due to the publication of key works by Anderson and Gellner in 1983. Are there other works in political science that have generated similar responses?

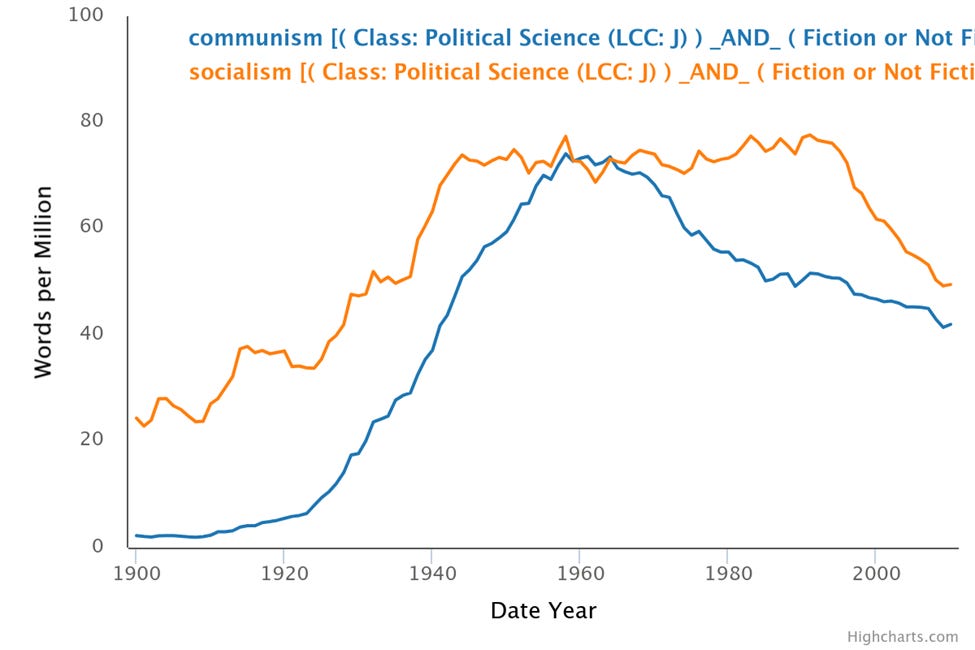

The fall of communism

Use of both ‘communism’ and ‘socialism’ has declined, though the trends do not precisely correspond to the end of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989. On the one hand, use of communism started to decline in the 1970s (perhaps the end was becoming more apparent), while socialism only began its decline in the mid to late 1990s. I did a deep dive on these terms elsewhere.

Terrorism and genocide

References to ‘terrorism’ emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, but their greatest increase was in the 1990s. I would have expected 2001 to be more visible, but terrorism captured our attention before then. Genocide has been steadily increasing since WWII with perhaps an inflection around 1980. I am not sure why. I expected Rwanda to be more visible based on my reading of the literature.

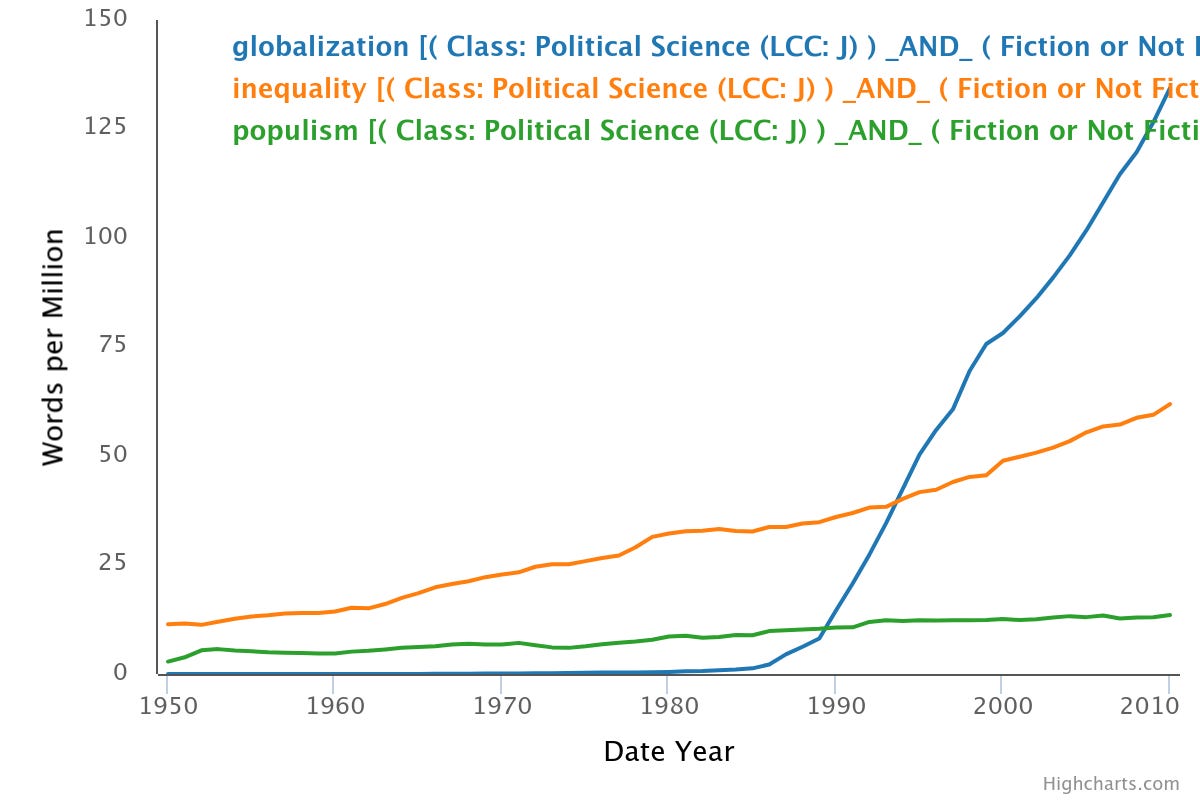

Current problems

Of the issues which dominate political science today, ‘globalization’ is the one that has most captured attention, particularly after 1990. ‘Inequality’ used to be the leader and it is the tortoise of the group with slow but steady progress rather than any clear reaction to the 1970s increase identified by Piketty. References to ‘populism’ are increasing but at a low level and rate. The data, however, ends in 2010.

The rise of China

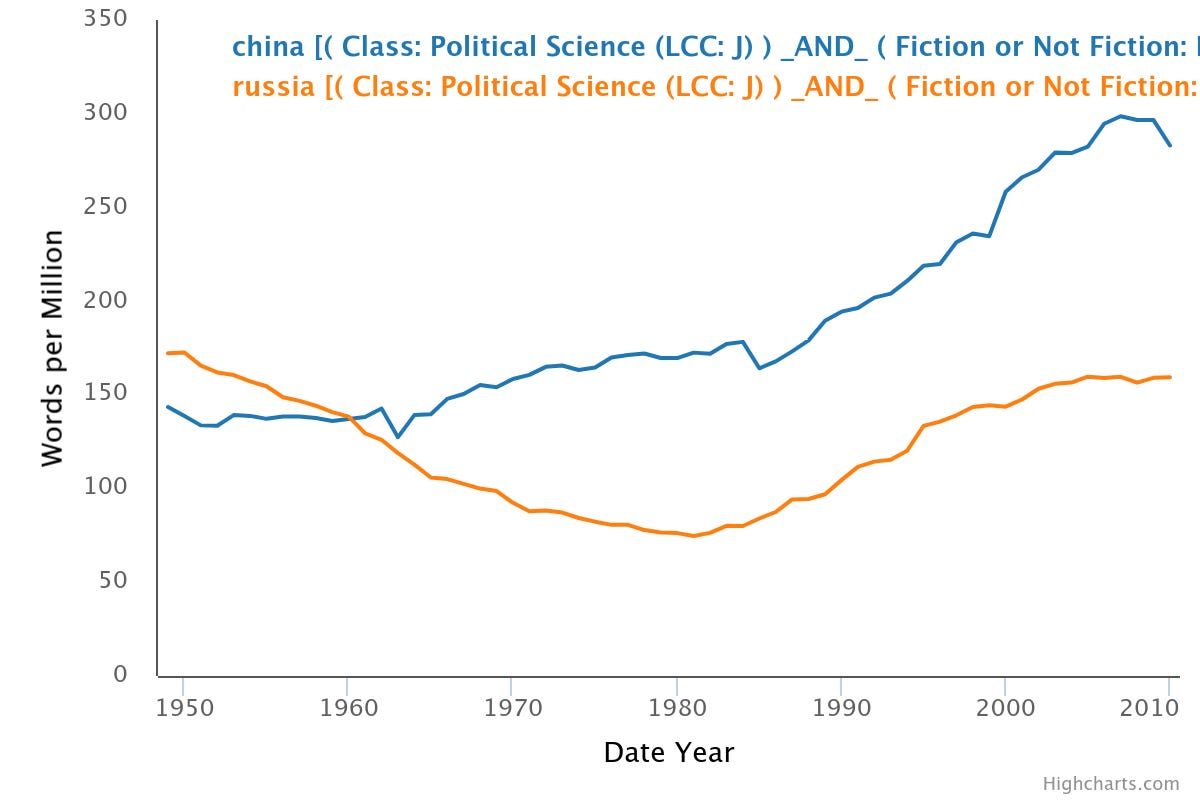

Considering individual countries, we can see China becoming more prominent since Deng’s reforms. Russia meanwhile lags perhaps as it lost its great power status, though the name change from USSR to Russia makes trends harder to parse.

Miscellany

There were a few other issues I was curious about. Have our normative concerns changed over time - for example, our concern with liberty relative to equality? Have we changed our focus on different institutional parts of government?

Freedom versus equality

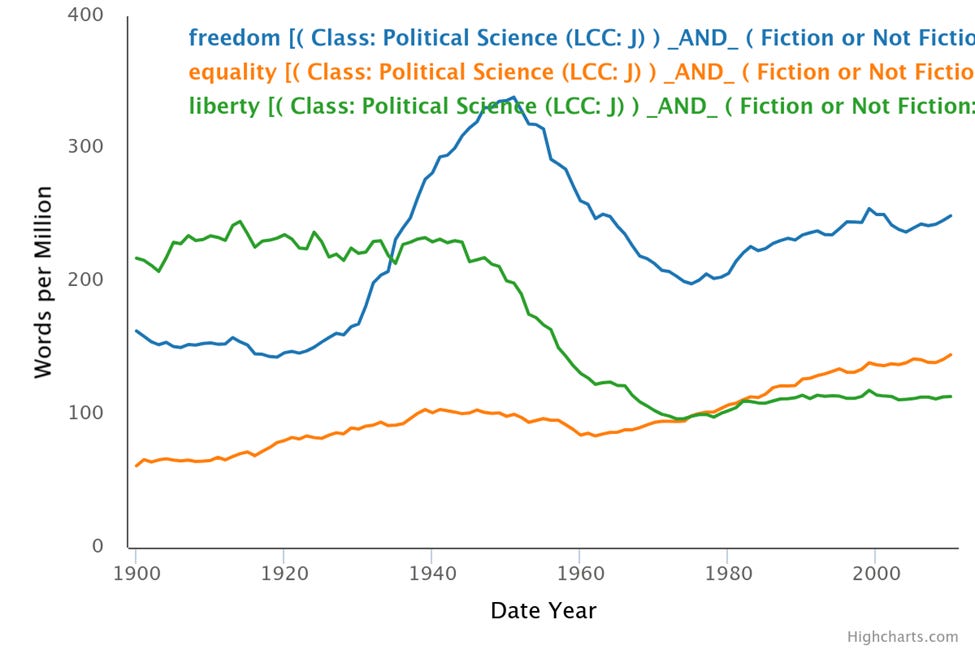

In terms of normative commitments, ‘freedom’ leads the race with ‘equality’ for the past century with the main changes being a bump for freedom in the 1930s and 1940s and a steady decline in the word ‘liberty’. Equality has steadily become more popular but at a lower rate and level.

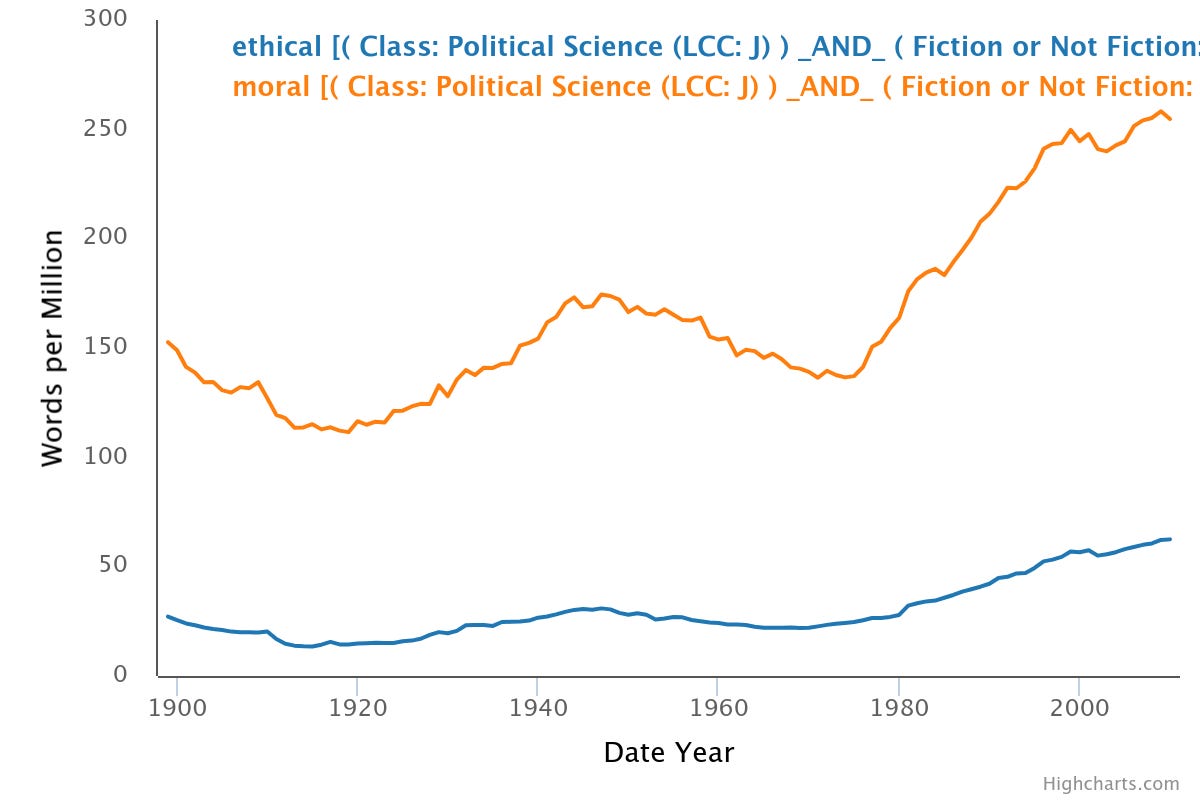

Contrary to the claims of Straussians that political science has ignored morality, we can see increases in references to both ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’.

Branches of government

I was surprised to see declines in the use of ‘executive’, ‘legislative’, and ‘legislature’ for much of the past half century. Are we studying them less or using different words for them? I had expected rising attention to executives.

Conclusions

To recap, some of the standard history of political science seems to be confirmed by these searches of texts. In particular, the behavior revolution, the study of development, imports from other fields, the rise of identity politics, and more attention to methods were all relatively visible at the expected times.

There was less clear evidence for the return of the state or institutions and the replacement of cultural approaches by rational ones, though it would be perverse to say that those movements were not important. A more nuanced judgment would be that they built on previous trends, they may not have been as quantitatively dominant as we remember, and they may have been more important in elite forums.

There was less support for some standard criticisms of the field. We have continued to refer to many of the areas that are purportedly neglected: power, administration, public policy, local politics, and leaders. The best that one could say is that this work became less prestigious and less innovative, but that is more speculative.

Finally, there is evidence that we are responsive to real-world events. This was clearest for democratization, the World Wars, globalization, and the rise of China. In some cases, the timing, however, was not exact, for example, writing about terrorism, genocide, inequality, and the fall of communism.

I will save my biggest caveats for last. There are always concerns in textual analysis that the composition of the database is driving trends. This could be due to the way the database is compiled or where people publish. This is somewhat less of a concern with the Hathitrust than with Google ngrams, but it always hangs over the method.

I probably should replicate the analysis using the database more directly rather than through the Bookworm interface.

Speaking of next steps, I should also try to do more topic modeling to see how these words are being used and how they relate to each other. I should also probably vary the metadata limits more - the specific presses and Library of Congress codes to get a sense of robustness. Some of these steps are a bit beyond my abilities, so hit me up if you are interested. I’m always happy to collaborate!

Technical notes: The HathiTrust is a large collection of digitized texts from research libraries. I used the Bookworm application which allows single word searches in the database. I limited the searches to books cataloged as political science (Library of Congress J) and published by university presses and major commercial presses. I included commercial presses because they were more popular in the past. I also ran the analyses with only university presses. I was compelled to specify presses because otherwise many government documents are included in the political science category. A list of presses is in the appendix.