Like many others, I’ve been enjoying Tyler Cowen’s GOAT: Who Is the Greatest Economist of All Time and Why Does it Matter?, an entertaining and erudite tour of the great economists inspired by Bill Simmons’s The Book of Basketball. I’m not enough of an economist to directly assess it, but I did want to comment on one aspect of it.

Cowen takes seriously the idea that the greatest economist, or presumably any economist who wishes to be great, should have a reasonable understanding of politics or let’s say political economy. Though this is not explicitly one of his criteria for evaluating them - perhaps only in his decision to consider how each of them deals with the issue of India - it is one that comes up frequently in his discussions.1 Some version of the word politics shows up 130 times in the text.

My aim here is to try to evaluate each of his candidates - Milton Friedman, John Maynard Keynes, Friedrich Hayek, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Malthus, and Adam Smith - based on their understanding of politics. Which of the great economists is the best in thinking about politics? I will mainly rely on the information that Cowen provides rather than striking out on my own. While I’ve read work by all of his candidates, I’m far from an expert on any of them.

Of course, assessing them in this way presumes that we have some idea of what it means to be knowledgeable about politics. While there is no right set of standards, I’d put forward the following six criteria as evidence of a strong understanding of politics.

Normative commitments. I would put an embrace of liberal rights and democracy at the forefront and perhaps, as Cowen puts it, a low degree of cancelability.

State capacity. The economist should have an appreciation of the importance of a state strong enough to ensure order and enforce the law.

Coalitions and interest groups. The economist should understand how sustainable policy making requires building coalitions and dealing with interest groups.

Public choice and incentives. They should understand that politicians are often motivated by self-interest and need to be incentivized to do the right thing.

Identities and the non-rational side of politics. They should recognize the importance of particularistic identities and psychological biases and how they impact politics.

Political skills. The economist should have some personal success putting their ideas into practice.

To preview the result, overall the candidates scored relatively well on these criteria, though most have at least one blindspot. Friedman is weakest on state capacity and identity, Hayek on normative considerations and coalitions, Mill and Keynes on public choice, and Smith on political influence (Malthus is harder to evaluate).

Based on Cowen’s material Smith might be the winner in straightforward scoring, but despite the flaws that Cowen identifies, Mill reaches greater heights, which is probably why he is the most studied by political scientists and why Cowen calls him “the best thinker about the world” among the candidates. He would definitely be my choice as GOAT even if political scientists should draw insights from all of them.

I’ll consider the candidates in the order that Cowen presents them, starting with Friedman.

Milton Friedman

On the positive side, Friedman was quite influential politically, which means that he must have had some understanding of politics. Policies where his influence was important were the end of the military draft, the negative income tax (the EITC), school choice, and for a time Federal Reserve policy. Even more generally, Cowen praises how he ushered in “much-needed market reforms”. Friedman, along with Hayek, was certainly an inspiration for reformers in Eastern Europe, most famously Václav Klaus.

His influence though appears to be mainly as a persuasive speaker rather than through behind the scenes coalition building (contrast Keynes below). We might call him a successful political entrepreneur. He was a skilled debater and proselytizer.

These skills, however, sometimes deserted him. He could be caught flat-footed when forced to defend his belief in freedom philosophically and to recognize tradeoffs between liberty and other values. Similarly, his views of human nature, identities, and biases in thinking seem to be rather stunted as evidenced for Cowen by his unimaginative autobiography.

Friedman certainly understood that incentives were important in politics. His critique of socialism saw the difficulty in motivating planners (as opposed to Hayek who focused on information problems). He was acutely aware of the power of interest groups in politics, for example, in his analysis of professional cartels.

Though Friedman is criticized for his visit to Pinochet’s Chile, Cowen defends him as standing staunchly in favor of the idea that economic and political liberty were inseparable. He is labeled along with Smith as among the least cancelable candidates.

Cowen is more critical of his advice to China which neglects the importance of state capacity. One could probably argue that Friedman suffered from Cowen’s libertarian vice which is to assume that the quality of government is fixed. In fact, some governments are more capable than others and government quality can be improved. Just consider Singapore.

John Maynard Keynes

According to Cowen, Keynes’s vice is the exact opposite as can be seen in his views of India. He expects India to be run from Whitehall by wise and caring bureaucrats like himself. His thought as “a whole stressed how experts could obtain enough knowledge to set things right.” While this is sometimes correct, for example, during the Great Depression or at Bretton Woods, it was of course more problematic in his view of colonialism as “settled, humane, and intelligent government”, even if one worries about the counterfactual.

In short, public choice or incentive considerations seem to be missing from Keynes’s view of the world. And this emerges again in his support for eugenics, which could be and was used by politicians for very bad ends. His objections to communism meanwhile were more aesthetic - it would limit character development - than based on incentives or information. In Cowen’s words, “he didn’t have a deep enough, or dare I say cynical enough, understanding of political economy and the incentives of government.”

Of course, this conflicts with Cowen’s claim that Keynes “had a keener understanding than Friedman did that a macroeconomic policy has to be both politically sustainable and also politically marketable.”

Keynes is even more impressive than Friedman as a political actor. This can be seen in his work in fighting the Great Depression, in WWII planning, and at Bretton Woods. He seems to know how to construct coalitions and viable programs, what Riker calls heresthetics.

Some of this may be attributable to his acute understanding of political psychology, as in his Essays in Biography, though one might wonder whether seeing politics in terms of the personalities of its protagonists is the best way to go about things. His broad interests suggest an appreciation for the variety of identities and ways of thinking.

Ultimately, Cowen judges that Keynes was “too willing to market his ideas at the expense of ideas of liberty, and insufficiently suspicious of state power.”2 Alternatively, he had an “excessive trust in a particular kind of authority, and imagin[ed] himself and his associates at the steering wheel of power.” He may not have internalized the message of Federalist #10 that “enlightened leaders will not always be at the helm.” Perhaps the problem is that he reasoned differently when thinking about the worse off and those at his own level.

Paradoxically, he is the one GOAT candidate about whom Cowen writes that his “poor understanding of political economy harm his GOAT potential,” even though he was by far the most politically successful.

Friedrich Hayek

Like Friedman, Hayek was perceptive about the ways that communism would not work - indicating an understanding of public choice theory - though he focuses on the information side of the problem and how the economy is less an engineering than a discovery problem.

He could be insightful about politics, for example, in the idea that powerful governments attract the worst politicians, a version of the adverse selection problem. Unlike Friedman he doesn’t “assume that all politicians are the same in quality” and he asks that we “evaluate constitutions by thinking about whom they might attract and repel when it comes to the quest for public office.” Americans in particular might think about this. Cowen does criticize Hayek for providing some cover for Pinochet’s regime, though he criticizes Stiglitz for doing the same for China.

Though he is probably the GOAT candidate who thought most about politics and wrote books with titles like The Constitution of Liberty, it is harder to pull a simple political theory out of his work. Cowen says that he doesn’t provide a set of criteria for determining when liberty or government should win out even as he renders judgments on all manner of public policies and not always in favor of free markets. This is because he is not willing to accept either utilitarianism or strong natural rights.

Overall, “Hardly anyone agrees about how much the basic insights can be stretched to understand politics.” The best case, not made by Cowen, might be his influence on Elinor Ostrom’s work on polycentric governance which builds on Hayekian insights on decentralized orders. Brad Delong similarly sees James Scott’s influential Seeing Like a State as inspired by Hayek. However, Cowen is probably right that states don’t fit well into the dichotomy of rationally constructed versus decentralized orders. They have elements of both. Cowen characterizes Hayek’s main normative message as “Stop” or “Worry” or “Liberty”.

While these views are at least intelligible, I had a harder time in understanding Hayek’s thinking about human nature even though Cowen spends significant space on Hayek’s book on psychology. Presumably Hayek’s critique of rationality meant that he recognized a variety of motivations, but he seems less than generous to those who disagreed with him.

Hayek’s influence on actual politics does not appear very strong, though some reformers, like Milei in Argentina today and some postcommunist figures, took him as inspiration.

John Stuart Mill

Mill should be the obvious winner of this contest. His contributions to political science are foundational, both On Liberty and Considerations on Representative Government. He developed some of the central arguments in favor of a free and democratic society and Cowen calls these arguments better than those made by Friedman or Hayek. His arguments for women’s rights are similarly essential. Cowen shows how he was always thinking in terms of bargaining power and secondary consequences of actions, both central to political science. And he lived these ideals in his one term as a member of parliament.

Cowen’s main gripe against him is his acceptance of colonial rule in India. Though Mill understood the incentive and informational problems of British rule, his flaw is “intellectual voluntarism”, which might be summed up in his claim that “When able to understand what justice requires, liberal Englishmen do not refuse to do it.” Of course, this applies to his views of British rule of India and perhaps Ireland rather than Britain itself where he embraced representative government (though some might criticize his advocacy for plural votes for the educated).

Cowen writes that he did not have enough understanding of public choice or how governments worked, but again this seems to be less of a problem when thinking about his own country. Like Keynes, his normally acute critical abilities suffered when looking outside the West, though he did not view Indians or others as inherently inferior. I think Cowen may be judging him too harshly.

Cowen emphasizes the issues of character development and civilization as central to Mill’s thought and while he does not criticize them, others might see them as problematic. They are certainly not emphasized in modern political science with a few exceptions (like James Q. Wilson or maybe Putnam). He does praise Mill for his understanding of behavioral economics and various biases in belief formation. This understanding, among others, makes him “the best thinker about the world” among the contenders.

Thomas Malthus

It was difficult to extract a sense of Malthus’s political thinking from GOAT. The best case that one might make is his understanding of how much political order and international peace depend on the environment and prosperity. Like Hayek, he is skeptical of utopian schemes and he opposed slavery. He understood culture as a motivating force, but in an overly moralizing way. As someone who hasn’t read much Malthus besides the famous extracts, I can’t say much more.

Adam Smith

Cowen surprisingly begins his chapter on Smith with a focus on Smith’s arguments in favor of a standing army. Smith sees national defense as vital to a country, more important even than prosperity. This jibes with the centrality of states and state capacity in political science and it is not clear that the other contenders show a similar level of concern about this.

Cowen also emphasizes Smith’s efforts to help people overcome the problem of local perceptions, which suggests a strong understanding of biases in psychology (indeed, he also wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments). Though he pushed people in the direction of more global views, he is also realistic about the difficulty of creating cosmopolitan or stoic citizens.

Smith performs well in his understanding of interest group politics, for example, in the way that mercantilism will not only have bad first order effects, but will also empower groups who benefit from it (a preview of this year’s Nobel Prize). Unlike Keynes and Mill, he recognizes the poor incentives of the East India Company and the inherent agency problems of their rule. For his opposition to slavery and colonialism, Cowen calls him, along with Friedman, the least cancelable of the great economists.

While he is not the GOAT economist because he is “simply the worst or second worst economist” of any on the list (Malthus would be the other), he does better in understanding some of the fundamentals of political science.

Others

Cowen doesn’t provide enough discussion of other contenders to allow an assessment. Samuelson loses major points in his book for not understanding either the incentive or informational critiques of communism and believing it to be a workable system. Arrow’s impossibility theorem is criticized as not as important as it first appears, though not wrong. Becker and Marshall’s politics are not discussed, though I would guess that Becker could be assessed given the volume of his writings including his erstwhile blog with Richard Posner. I would imagine that like Friedman he is strong on interest groups and public choice and weaker on state capacity. Schumpeter of course made major contributions to political science, most famously his theory of democracy, which is not discussed.

Summary

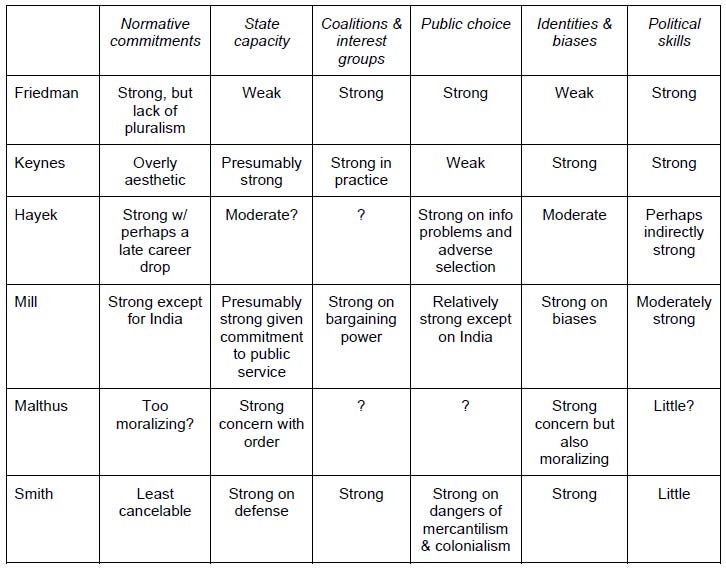

How do the GOATs overall perform when we assess them according to the six criteria? The table below summarizes my assessments (again based mainly on information from Cowen).

Normatively, they are relatively good. Cowen notes that all of the major GOAT contenders pay attention to the idea of a “free, open liberal democratic society.”

Despite the libertarian bent of economics, the GOAT contenders are relatively strong on the importance of state capacity with exceptions for Friedman and possibly Hayek.

Many seem to recognize the role of coalitions and interest groups, though few make it a major theme. Friedman, Mill, and Smith do best here.

Public choice considerations are prominent in most as well, though sometimes weaker for those who put faith in experts like Keynes and Mill. They are naturally strong for libertarians like Friedman and Hayek.

The importance of identities and biases play a much greater role for the 18th and 19th century GOAT candidates like Smith and Mill than for the 20th century ones who didn’t have time to imbibe behavioral economics.

In terms of political skills, Keynes and Friedman stand out and Mill had some success. Perhaps Hayek had some indirect success, while the rest seemed less interested.

If we were to use understanding of politics as the key criteria for the GOAT, Smith might come out as the winner with Mill a strong competitor. Smith’s only failing was as a political actor and Mill mainly fell short in his views on India and Ireland. As I mentioned at the start, I would probably elevate Mill given the depth of his thinking about politics and his foundational ideas on liberty and representative government.

This may not be surprising given that they are the two thinkers who are assigned most frequently in political science classes. The others, however, all offer important perspectives that political scientists should take seriously even if there are gaps in their thinking.

I’m curious how this exercise would turn out if I flipped the question and asked how well the GOAT political scientists understood economics. I have my doubts.

His criteria are: “The economist must be original, of great historical import, serve as a creator and carrier of important ideas, have a hand in both theory and empirics, have a hand in both macro and micro, and be “not too wrong” on the substance of issues. Furthermore, the person also must be a pretty good economist! That is, if you sat down with the person and discussed economic issues, you would be in some way impressed.”

He cites Keynes’s anti-semitism, support of eugenics, and passages from the German translation of the General Theory.

Without British colonialism it is hard to imagine that India would be either unified or a fairly stable democracy. Look at what happened in the other medium to large Asian nations that were not colonized by Western countries: Afghanistan, Iran, Japan, Korea, Thailand, Turkey, and, probably most relevant because of its scale, China. Without the unified government and the English language that British colonialism brought it is hard to see how India could have become unified. (English has been an important unifying factor and bridge to the rest of the world even though few Indians actually speak English as their first language.) And of the countries I listed, only Japan is a stable democracy, and that it because the United States imposed it during its post-World War II occupation of Japan. (Korea is half a stable democracy -- the southern half.) The counterfactual without British colonialism might well have been the kind of turmoil that China experienced, resulting in tens of millions of deaths.

Jevons?