I expected bad things from the second Trump administration. Simply taking Trump at his word was enough for me plus knowing that he would face little pushback from his own party, that only sycophants would be willing to work for him, and that he had accumulated many grievances and a strong desire for revenge.

But that things would be quite this bad was still something of a shock. The attempts to end birthright citizenship, suspend habeas corpus, reassert the budgetary authority of Charles II, threaten the takeover or destruction of private institutions, and impose massive tariffs under dubious authority were all something of a shock.

Yes, the first term had its share of weirdness, but it also confirmed some of what we know about US politics. Matt Glassman has been eloquent on this point. In many ways, Trump was a weak president who accomplished little because he didn’t understand how to gain and use power. He was a negative confirmation of Neustadt’s theories of presidential power. It seems like those days - when political science could shape our understanding - are gone.

The shock tells me that there must have been flaws in the way that I and others were looking at politics. As a good Bayesian, I decided to revisit my theories in light of this new evidence. Which theories have suffered the most under Trump’s onslaught and require rethinking? Here are some that occurred to me and there are surely more.

Theories that Trump overturns

Democratic consolidation

The idea that democracies can be consolidated, that they become the only game in town, has perhaps suffered the most. If democracy can be imperiled in the oldest democracy in the world, then the concept of democratic consolidation as something distinct from simple democratic survival is pretty much dead.

The liberal tradition

Louis Hartz famously argued that American political culture was dominated by a liberal tradition. That idea has long been criticized (see Rogers Smith among many others), but public support for Trump’s illiberal actions - from his shakedown of private institutions to suspension of habeas corpus - seems to have put the final nail in the idea that America’s traditions are essentially liberal.

The power of the rich: preferences

Probably the most striking political science finding of the last twenty years has been evidence (courtesy of Marty Gilens with assists from Larry Bartels and Ben Page) that public policy is much more responsive to the preferences of the rich than to the middle class and particularly the lower class. On the surface, Trump seems like confirmation of this work - he is himself a billionaire who won the election with a large assist from other billionaires and has made them his top advisors.

But, his policy choices contradict the policy preferences of the rich almost across the board. The rich prefer an open economy, free trade, the availability of immigrant labor, and a functioning state, all issues where Trump has taken the exact opposite tack. Yes, the rich got some of what they wanted - most prominently a crackdown on wokeness - but Trump has resisted what is perhaps their strongest and most distinctive view, their desire to tear down the welfare state. In short, policy under Trump is not a product of what the billionaires want, but some combination of the very idiosyncratic preferences of one billionaire with some help from the median voter and their anti-trade, anti-foreigner, and anti-wokeness vibes.

The power of the rich: quid pro quos

This doesn’t mean that the rich are helpless. In fact, the Trump administration also contradicts the finding that quid pro quos between business and government are relatively uncommon in the US (or very well hidden). This may be sound surprising given that most people believe politics to be mainly transactional. But political scientists have typically failed to find systematic evidence connecting money and policy actions in the US (see Weschle for a counter). Instead, they often explain political contributions as motivated more by ideology and lobbying more as the provision of information or as a legislative subsidy.

Under the current Trump administration, quid pro quos couldn’t be more obvious. Trump has signaled that he is open for business and has provided favors and exceptions for contributions to his various slush funds (his inaugural committee, his fake lawsuits, his cryptocurrency). The rich and foreign governments thus get some of what they want in exchange for direct payments unless that contradicts what the supreme leader wants.

Gridlock

Gridlock has long plagued the US political system and things have only gotten worse in our era of polarization. Who knew the solution was sitting right there in front of us. Simply allow the president to usurp legislative powers and ignore laws or the Constitution while relying on majorities in Congress and SCOTUS to play dead. Yes, things have been trending in this direction for some time - the imperial presidency and all that - but who knew that presidents could simply assert the monarchical powers hidden in our system. Maybe change is slowing down as the courts and perhaps Congress get their bearings. And very few of these changes are anchored in laws. But the country looks very different today than it did a few months ago even as Trump controls the thinnest majority in Congress.

Liberalism and realism in international relations

The liberal school of international relations has long seen the US as a force for good in the world and international institutions and cooperation as a key achievement of the postwar order. Trump’s attempts to destroy this order and shakedown each and every country provides, on the one hand, belated proof that the US was often a force for good and, on the other hand, evidence about how much the postwar order depended on our good will. Trump’s behavior is exactly what people like Noam Chomsky or Chalmers Johnson always attributed to the US. They may claim vindication, but I’d say that it goes to show that we weren’t always like that. (Just note the degree of shock in Europe.) And this isn’t to say that realism looks any better. A realist arguably would have expected Trumpian administrations to be much more common. Why did it require the election of a Trump to finally exploit our power in this way?

American exceptionalism

The joke going around political science is that scholars of the politics of foreign countries (comparativists) were much better prepared for Trump than scholars of American politics. I’m not sure if that is true, but a working knowledge of democratic breakdown, clientelism and corruption, populism, illiberalism, and repression are certainly helpful in understanding our current times. If there was an exceptionalism in American politics, it seems long gone.

Theories that Trump confirms

Are there any theories that Trump has helped to confirm? I could think of a couple.

Affective polarization

The hearts and minds theory of polarization seems to have emerged victorious over a more rational, running tally approach. Supporters of Trump in particular seem immune to evidence of his failures, though we can hope that his teflon is not impervious.

Policy seeking theories

Policy seeking theories of political behavior seem to have gained support relative to theories focusing on office (or reelection) motivations. Trump (and Republicans) could easily have benefited from a strong economy, but they instead decided to destroy it and presumably their hopes of winning in 2026. (Perhaps a reelection theory that focused on the Rust belt could survive this onslaught.)

Thermostatic public opinion

A couple of colleagues mentioned to me that public opinion seems to be responding to Trump in thermostatic ways. His extreme actions have led public opinion to move in the opposite direction. We can only keep our fingers crossed that this continues.

Public choice

Public choice scholars who are hyperaware of the dangers of putting powers in the hands of the government seem to have been proven correct.

Concluding thoughts

Given this destruction, how should we start to reconceive political science? I see two possible paths.

On the one hand, Trump may simply be sui generis. Under most plausible counterfactuals (from Romney winning in 2012 to a successful impeachment in 2021 to an assassination in 2024), I don’t think we end up in this situation. Perhaps only the illiberalism persists under other Republican administrations.

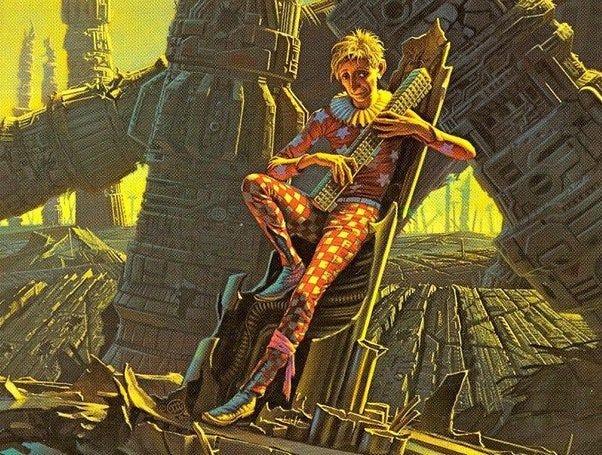

Indeed, the situation reminds me of Asimov’s Foundation books where Hari Seldon formulated the laws of psychohistory that perfectly predict the future evolution of civilization. But along comes the Mule, a figure who could not be predicted and who upsets all of these laws. Trump seems like a Mule-like figure (or a black swan if you are a Taleb fan) who certainly has roots in American traditions, but who is also far outside of the norm. Indeed, it is hard to think of a successor who could do what he has done. Will Vance command this kind of support or push the same buttons?

If this is the case, rather than toss out our theories, we could preface them with a domain condition: our theories mostly hold unless a Trump figure wins the presidency. This seems ad hoc, but other fields sometimes do something similar. Krugman refers to the oddities of depression economics (life at the zero lower bound) relative to normal economics.

The other path is to take Trump’s challenge more seriously. One change that is often proposed is integrating American politics into comparative politics. Much of what we see under Trump is common in other countries.

Another change is greater attention to the importance of informal norms in politics. Trump is a serial norm breaker and thus shows how important they were.

All of these possibilities seem like small beer compared to the current challenge. But what other options do we have?